To the TIDE Blog...

Mar 9 2022

Undergraduate Showcase: Curating Transculturality

For two weeks in February 2021, undergraduate students on the third-year ‘Researching the Renaissance’ course at the University of York became honorary TIDE researchers. Lauren Working introduced them to several aspects of the project, particularly TIDE's Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern England and TIDE's collaboration with the World Museum. In the first week, students used Keywords and case studies to research English travellers to Central and South America in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In the second week, they curated exhibitions based on their findings. Presentations ranged from an analysis of Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko (1688) alongside the material culture of feathers and garters, to an analysis of Walter Ralegh’s Discoverie of the Large, Rich, and Beautiful Empire of Guiana (1596) through a consideration of the use and value of gold in Indigenous, English, and Spanish material culture. Below, third-year student Grace Dye presents her group’s research on pearls.

Pearls and Empire

Prompted by our reading of the 1592 account of the English capture of the Portuguese ship, the Madre De Dios, published in Richard Hakluyt’s The Principal Navigations (1599), we were fascinated by the range of objects listed in the account, and chose to research more about the circulation of pearls. It was important for us that we think about the dangerous labour and production that underpinned the pearl trade, and not just their associations with beauty and luxury in European literature and art.

Figure 1. Standing Ram Pendant, British Museum, donated by Ferdinand Anselm Rothschild. The above pendant from the British Museum is believed to have been made in Spain during the 1500s with pearls sourced from South America.

Figure 1. Standing Ram Pendant, British Museum, donated by Ferdinand Anselm Rothschild. The above pendant from the British Museum is believed to have been made in Spain during the 1500s with pearls sourced from South America.

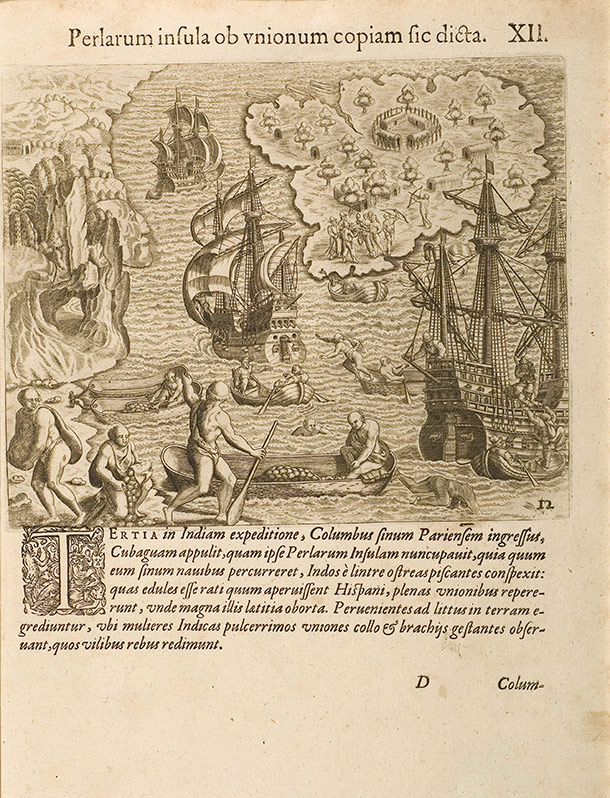

Figure 2. Pearl fishing in the Caribbean, from Les Grands Voyages (1590).

Figure 2. Pearl fishing in the Caribbean, from Les Grands Voyages (1590).

Figure 3: Illustration of the Koh-i-Noor on display at the Great Exhibition, featured in Illustrated London News (1851). Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Figure 3: Illustration of the Koh-i-Noor on display at the Great Exhibition, featured in Illustrated London News (1851). Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Grace Dye