The fifth century BC Greek author Herodotus was one of the earliest chroniclers of man-eating. ‘Beyond the desert the androphagi dwell’, he wrote. ‘The androphagi have the most savage customs of all men: they pay no regard to justice, nor make use of any established law. They are nomads and wear a dress like a Scythian…and of these nations, are the only people that eat human flesh’.[1] Their willingness to consume human beings was the trait that most characterized the world’s most ‘savage’ inhabitants. The essence of the man-eater lay in his or her name: anthropo, meaning human, and pophagy, feeding on or consumption. Invoked in philosophical treatises, travel narratives, epic poetry, and political works by Aristotle, Pliny, and Juvenal, man-eating described those who lived on the margins of civil, and therefore political, societies.[2] The recurrent associations between cannibalism and brutality appeared almost universally in subsequent usages. While man-eaters or anthropophagi appeared in Greco-Roman literature, the linguistic base from which canibe or cannibal derived likely came from Columbus’s term for the Caribs he encountered in the West Indies.[3] Although notions of man-eating had a wide geographic reach prior to European intervention in the Atlantic, therefore, the term ‘cannibal’ itself was a product of European encounters with indigenous Americans.

In the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, English authors began to use this particular term and its associations to denote a wide range of social, religious, and political transgressors. If the writings of polemicists were taken literally, then cannibals were to be found in parish communities, Catholic churches, and the royal court itself, where metaphors of ripping bodies apart resonated with deep social and economic change in England. Discussions of cannibal behaviour became related to discourses about citizenship and society – about the bounds of civil society, and who might live within it. This complicates postcolonial scholarship on the cannibal as the ultimate ‘other’, which maintains that cannibals are understood purely in terms of European dominance and power. A distinct relationship certainly existed between the conquest of other territories and peoples, and the (supposed) proliferation of cannibals in those regions, as the literary scholar Stephen Greenblatt and the anthropologist William Arens have argued.[4] George Peckham, promoting English activity in North America in 1578, professed that ‘Christians may … justly and lawfully ayde the Savages against the Canniballs’.[5] Meanwhile, cases of English colonists resorting to eating human flesh during the Starving Time of 1609/10 in Jamestown, reported by John Smith and the governor George Percy, broke down neat dichotomies of ‘civil’ Englishmen and ‘savage’ others.[6] In England, Protestant writers frequently used ‘cannibal’ to describe the Catholic belief in transubstantiation, in which the bread and wine of the Eucharist became the body and blood of Christ. ‘If the Canibals are to be abhorred, because they devour and eate mans flesh, their enimies whome they take in the warres,’ wrote Thomas Lupton, ‘are not you then much more to be detested, that are not ashamed to eate and devoure…the very bodie of Christ your great & high friend’?[7] Faithful Christians eschewed violence in favour of love, wrote Thomas Sanderson in 1611, rejecting the ‘mysticall and spiritual kind of murder and mangling’ that came from ‘a corporall feeding … [like] brutish Cannibals’.[8]

In other contexts, the ‘cannibal’ described larger societal divisions caused by the Reformation and the expansion of the early modern state. Those who practised enclosure and closed off public land, wrote the cartographer and surveyor John Norden in a popular devotional work, ‘were as good to say, hee would eate his flesh like a Canniball...Alas, what will a poore mans carkasse profit you?’[9] Ben Jonson’s plays, scathingly critical of money-grabbers and hypocrites, includes The Case is Altered, in which the miser Jacques cries to his daughter, ‘Wher’s my gold? … O thou theevish Canibal,/ Thou eatest my flesh in stealing of my gold’.[10] In Jonson’s The Staple of News, performed in 1625, Lickfinger is a cook and projector who proposes to go to America to convert cannibals. Hotly puritan and desiring to advance ‘the true cause’, Lickfinger acknowledged that it was ‘our Caniball-Christians’, rather than the ‘[s]avages’, who had to learn to ‘[f]orbeare the mutuall eating one another,/ Which they doe doe [sic], more cunningly, then the wilde/ Anthropophogi; that snatch onely strangers’.[11]

Indeed most English accounts of indigenous cannibalism focused on the violence more than the act of human incorporation. In An houre-glasse of Indian newes (1607), John Nicholl recalled being shipwrecked off the island of St Lucia in 1605, where the crew came into conflict with Carib Indians. Nicholl lamented being left ‘onely with a companie of most cruell Caniballs’, yet he did not purport to witness any man-eating ceremony himself.[12] Rather, it was Carib ‘tyranny’ in killing the shipwrecked English that most haunted him. Nicholl’s pamphlet served a didactic function not unlike early seventeenth-century writings on English captivity in the Ottoman Empire. The experience reinforced the Christian, usually Protestant, fidelity that brought deliverance in the face of hardship. ‘[L]et the Christian Reader judge’, Nicholl wrote, ‘in what a perplexed state we were plunged…without hope of ever having any meanes to recover the sight of our native and deare countrey’, until, through divine aid, friendlier peoples on the island provided succour.[13]

Instances of more nuanced representation also existed. The Elizabethan traveller Anthony Knivet lived among Tupi groups in Brazil in the 1590s. His account contained detailed descriptions of the habits and fashions of different indigenous groups across South America, where he ‘went naked as the Cannibals did’..[14] Knivet liberally and interchangeably referred to many indigenous groups as ‘savages’ and ‘cannibals,’ which seems to confirm European standards of civility against the supposed generalized savagery of indigenous groups. However, his willingness at the same time to use specific names for places and individuals – such as the Tapuia-speaking ‘Pories’ (Purí) and the ‘Wataquazes’ (Waitaká) – also demonstrates an awareness of the differentiation of indigenous identities. Knivet’s seeming interest in discussing indigenous groups served a practical purpose, providing detailed intelligence about Native groups that enabled him to participate in the capture and enslavement of indigenous peoples for the Portuguese.[15]

Back in Europe, the use of cannibalism as a means of self-reflection was evident in the French essayist Michel de Montaigne’s essay ‘Des Cannibales’ (c. 1580). Montiagne famously used Brazilian Tupis to critique his own society’s mores, specifically in the context of religious violence. ‘[A]s farre as I have been informed’, Montaigne posited, in the translation of his essays into English by John Florio in 1603, ‘there is nothing [in Brazil] that is either barbarous or savage, unlesse men call that barbarisme, which is not common to them’.[16] Montaigne juxtaposed the supposed ‘barbarous horror’ of cannibalism to the French wars of religion, where ‘I think there is more barbarisme in eating men alive, then to feede upon them being dead; to mangle by tortures…a body full of lively sense, to roast him in peeces…as we have not only read, but seene very lately, yea and in our own memorie, not amongst anciente enemies but our neighbours and fellow-citizens; and, which is worse, under the pretence of piety’.[17]

Within the English context, Shakespeare’s Caliban in The Tempest, whose name may be a play on ‘cannibal’ or its many variants, has generated much discussion. Written around 1610-11, The Tempest is a product of a culture that avidly consumed travel accounts, such as one of its possible sources, William Strachey’s ‘True Reportory’ (c. 1610), about the wreck of the Sea Venture in Bermuda in 1609. There is a telling ambivalence in its representation of Caliban as strange and other, yet ‘familiar’ and revelatory in the raking light he helps throw on the ‘civilized’ European people who find themselves on the island. This provides the backbone of the social and moral negotiations in the play. Caliban’s characterization shifts among multiple points. He is both new (a ‘strange fish,’ II.ii) and old (his mother is the witch Sycorax of Algiers (I.ii)). His actions move from savagery (he is accused by Prospero of attempting to rape Miranda, I.ii), and gullibility (‘[a] most poor credulous monster,’ Trinculo calls him in II.ii), to striking lyricism (‘the isle is full of noises,/ Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not,’ III.ii). Prospero’s words about him in the final scene of the play (‘[t]his thing of darkness I acknowledge mine,’ V.i) has been the focus of a significant body of scholarship that reads him as a part of an emergent colonial discourse.[18]

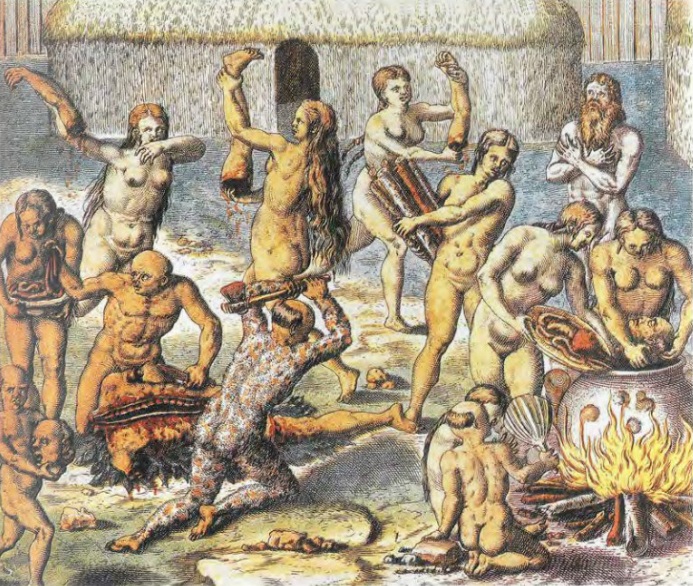

Scholarship has examined cannibalism through the lens of medical history, proto-capitalism, and religious confessional differences, but the physicality of cannibal behaviour emerges most strongly in many sixteenth and seventeenth-century usages.[19] It was the visceral embodiment of degeneration and the breakdown of civil society that most haunted English writers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, whereby communal acts of tearing apart other human beings (committed by men and women alike) seemed to represent the frightening promise of chaos and war. This vision of bloodshed must have seemed particularly terrifying to the English as they watched the wars of religion ravaging the Continent in the decades between the French war of religion and the Thirty Years’ War. In 1624, George Goodwin’s satires attacked transubstantiation in the context of Rome’s imperial supremacy, for what was the ‘[f]lesh-feeder’ but a ‘Popish Canniball’, sowing widespread violence?[20] While scholars should approach early modern sources purporting to witness cannibalism with caution, anthropologists and select indigenous groups have acknowledged the importance of human consumption as a cultural system in specific moments in time, in acts of warfare or commemoration.[21] The term ‘cannibal’ thus operated at a crossroads, relying on its associations to the lifeways of indigenous peoples while functioning as means for the English to reflect on their own capacity for violence, and their anxieties about the collapse of civil society.