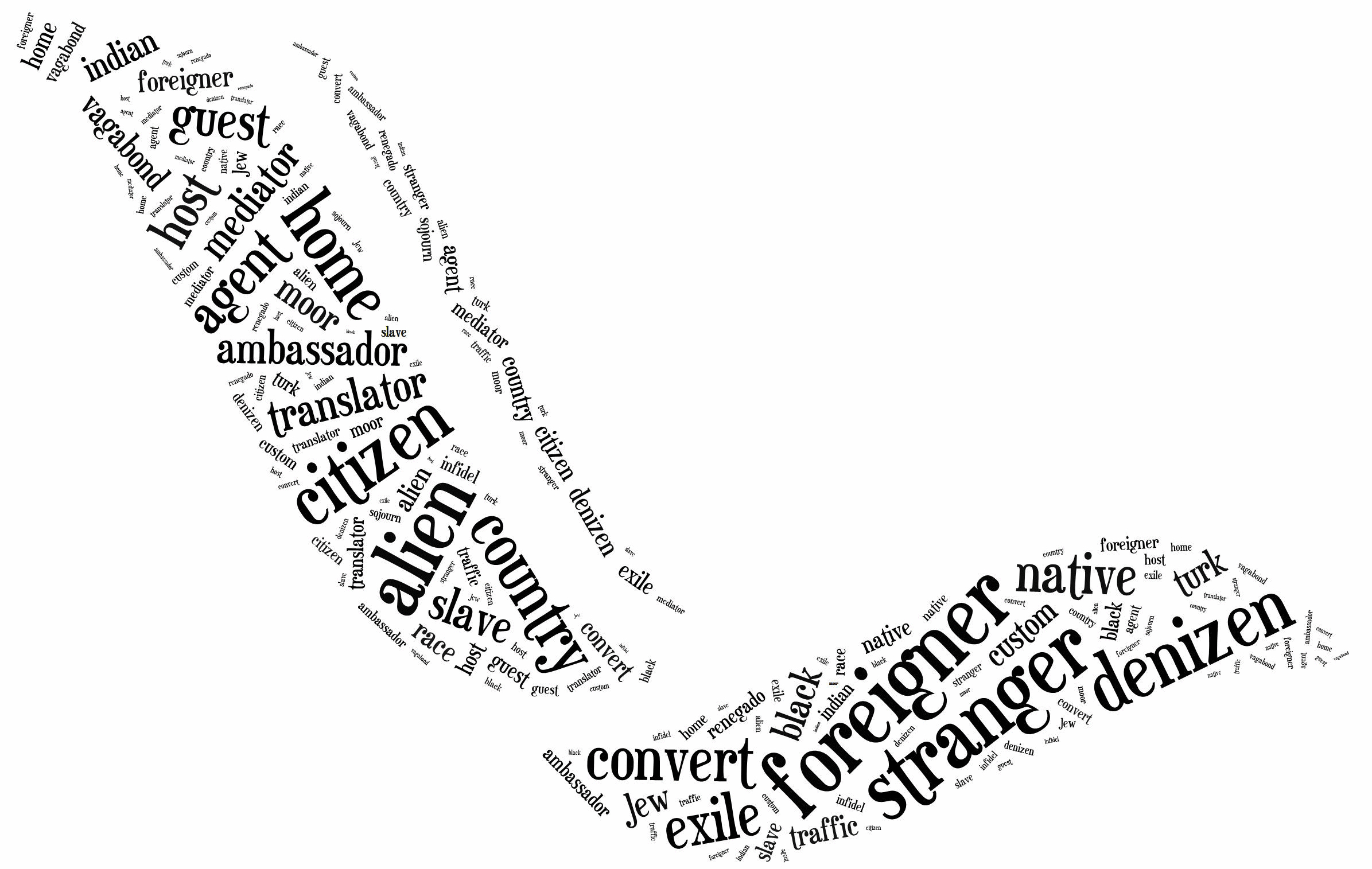

‘Turk’ was a mutable term in early modern England, difficult to untangle from a range of associations with Muslims, the Ottoman imperial state, and English converts to Islam.[1] ‘Turks’ were often synonymous with Ottomans and the power of Ottoman sultans, while Muslims from other ethnic origins in central Asia or Africa could also be described as such.[2] Elizabethan and Stuart encounters with Ottomans through popular print, sermons, travel literature, and plays revealed a rich, if at times contradictory, interaction with ideas of the Turk.[3] Alongside a sense of awe at Ottoman imperial power, there were accounts of pirates who converted to Islam, Englishmen enslaved on Ottoman galleys, and travellers such as George Sandys who, behind assumptions of Christian superiority, admired aspects of Muslim hospitality or charity. This was not a world in which Europe necessarily emerged superior.[4] The ‘mighty Empire of the Turks’, acknowledged the historian and translator Richard Knolles in 1603, was ‘the greatest terror of the world, and holding in subjection many great and mighty kingdoms’.[5]

English imperial rivalry with Spain in the Atlantic also implicated the Islamic world. Not only did the Ottomans serve as an exemplum for empire, but the English frequently relied on Spanish writings that positioned the Atlantic within a long history of Christian conquest and conversion against ‘Moors’, ‘Turks’, and ‘infidels’ in the East.[6] To many sixteenth-century Spanish authorities, colonization in Central and South America was an extension of centuries-old conflicts against Islamic peoples, as when the chronicler Francisco Lopez de Gómara wrote in the mid-1550s that the ‘conquest of the Indians began after that of the Moors was completed, so that the Spaniards would ever fight the infidels’.[7] The naval officer Richard Hawkins, complaining of his imprisonment in Seville in a letter Queen Elizabeth, criticized the prevalence of ‘Turks’ in the Mediterranean and accused Spain of being ‘peopled of a mingled nation of Moors, Turks, Jews & Negroes’, believing this caused civil unrest more than ‘domestic enemies’.[8] Hawkins’ letter evoked the transcultural Mediterranean world with its mixed ethnicities, where the range of Islamic, Christian, Jewish, and African beliefs and peoples were collapsed into uncertain categories whose identifications could hardly be encapsulated in broad terms like ‘Moor’ and ‘Turk’. [9]

While the English had encountered ‘Turks’ in the Mediterranean and at sea, Queen Elizabeth was the first English monarch to allow her subjects to trade and interact with Muslims without being liable for prosecution for dealing with ‘infidels’.[10] The creation of the Levant Company, a merger between the Turkey Company and Venice Company in 1592, led to a series of trade and diplomatic negotiations in transcultural contact zones.[11] This included Muslim powers such as the Safavids of Persia or the Mughals of India, but also significant contact with the Ottomans and North African Moors.[12] George Manwaring, who travelled to the Ottoman Empire and Persia in the retinue of the adventurer Anthony Sherley in the late 1590s, recorded an incident in which he used ‘Turk’ as a more disparaging term that contrasted with the identity of the janissaries, or elite soldiers, in Sherley’s company. ‘I met with a Turk’, Manwaring wrote, who insulted and struck him, after which a janissary rose to the Englishman’s defence and severely beat the offender’s feet until he could no longer walk.[13] Manwaring’s account evoked a system of honour and disgrace that undercut religious and political difference, in which the base or uncivil behaviour of the ‘Turk’, however gallant he had initially appeared, contrasted to that of the officers of the law. [14]

Portraying them as luxurious and ruthless in battle, the English admired ‘Turks’ for their military might and commercial potential.[15] ‘Who can deny that the Emperor of Christendom hath had league with the Turk’, Richard Hakluyt wrote in 1599. ‘...Why then should that be blamed in us, which is usual, and common?’[16] At the same time, English churchmen, travellers, and policy-makers often condemned Ottomans for their Islamic faith. Memories of the 1571 Battle of Lepanto, in which Catholic forces defeated the Ottoman fleet in the Mediterranean, still lingered powerfully over the European imaginary into the seventeenth century. In 1603, London printers reissued King James’ poem on Lepanto in the aftermath of his ascension to the English throne. Framed in highly biblical language, the heroic verse celebrated the ‘bloody battle’ between ‘the baptized race, / And circumcised Turban Turks’.[17] James conformed to commonplace assumptions that the ethnographic identity of the ‘Turk’ was inseparable from religion: ‘Are we not day by day / By cruel Turks and Infidels / Most spitefully opprest?’[18]

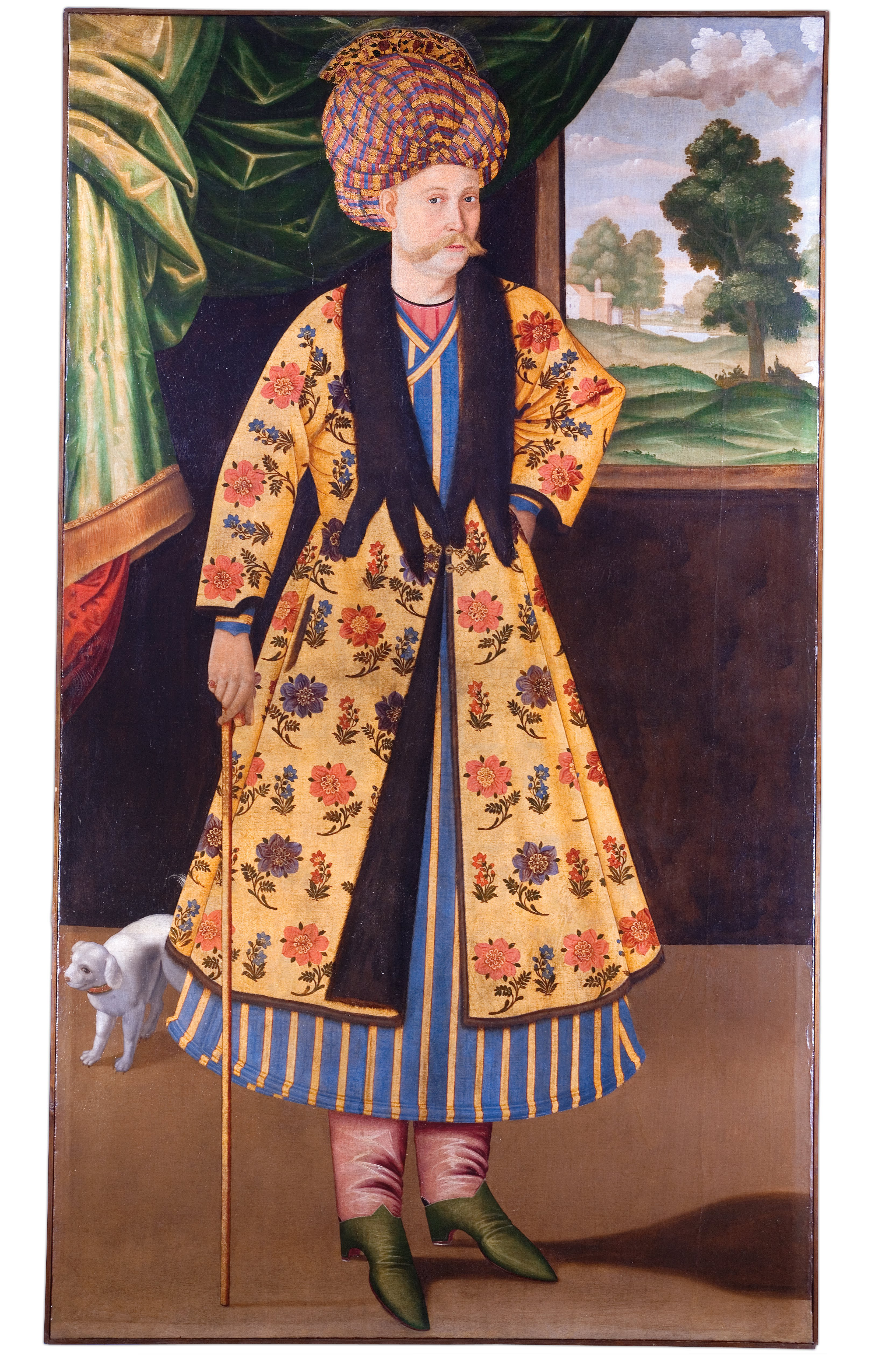

Beyond military strength and religion, visual differences set Ottomans apart. James I’s poetic reference to the ‘circumcized Turband Turkes’ captures one of the primary markers of the ‘Turk’ in early modern England: bodily modification and the turban. Costume books and cosmographies often visually depicted turbans as key markers of Turkishness.[19] The English considered the practice and ritual of circumcision to be a fundamental part of Turkish identity, a rite shared with Jewish practices that raised profound anxieties about English loyalties and the irreversibility of conversion away from Christianity. The pirate John Ward, for example, died in Tunis in 1623, having converted to Islam by 1610 and adopted the name of Issouf Reis. ‘[O]nce a great Pirate’, the Scottish traveller William Lithgow wrote, recalling his meeting with Ward in Tunis, ‘in despight of his denied acceptance in England had turned Turke, and built there a faire Palace, beautified with rich Marble and Alabaster...With whom I found Domestic some fifteen circumcised English Runnagats’.[20] Lithgow’s report acknowledged an uncomfortable truth: that a rejection of Christianity might actually lead to a prosperous life.

Ward gave Lithgow a magnanimous welcome, but English authorities in London viewed Ward’s willingness to ‘turn Turk’ as an act of damnation and disloyalty. Circumcision was an irrevocable act, a physical marker of the secret corruptions of the human heart, and plays like Robert Daborne’s A Christian turn’d Turke (1612) recast Ward’s trajectory as one that inevitably led to divine punishment. The malleability of the human body and soul to the customs of the Turk presented a problem in cases of English prisoners subjected to forced circumcision. When Richard Burges and James Smith, two young men captured in Tripoli in 1583, refused to convert to Islam, they were told ‘thou shalt presently be made a Turke’, implying that ‘turning Turk’ could be a forcible act wrought by physical change.[21] Afterwards, Burges strongly resisted this notion by proclaiming that although ‘they had put on him the habit of a Turk’, nonetheless a ‘Christian I was borne, and so I will remain, though you force me to doe otherwise’.[22]

Ward was a notorious pirate, and direct contact between Englishmen and Ottomans often happened at sea. Captivity accounts related the stories of fearful encounters between sailors and merchants that might lead to death or capture. Edward Webbe recounted his ‘time in the wars and affairs of the great Turk’ during and following his capture, narrating his travels through Damascus and Constantinople, Persia and the Mughal Empire, in service of the Ottoman army in the 1570s.[23] Webbe’s account suggests that English captivity narratives heavily shaped popular understandings of Islam in early modern England, portraying cross-cultural interactions in the highly religious, redemptive language of Protestant reform.[24] In the Tudor period, English writing about Ottomans focused especially on ‘religious animosity’ and the need to resist the seductive sway of the Islamic East.[25] The English state maintained that captives who had forcibly been turned Turk had not lost their status as subjects; they continued to be subjects of the English Crown.[26] On several occasions the crown sent officials to ransom English captives and converts in the hope that they would return to England and reconvert.[27] Since captivity narratives were a primary source of information about Ottomans in England, combatting the appeal of the Turk was closely related to the Protestant notions of conformity and steadfastness often disseminated in cheap print. The ethno-biblical perspective shifted under the Stuarts. By the 1640s, accounts often framed captives as explorers and adventurers who provided valuable intelligence about Ottoman affairs, particularly in matters of business and trade, the result of increased engagement with the Ottomans in the seventeenth century.[28]

Though the English encountered ‘Turks’ and ‘Mahometans’ in religious polemic, popular print, and travel and diplomatic exchange, large audiences also saw Ottomans represented on the stage. In plays, Islam became ‘a discursive site upon which contesting versions of Englishness, Christianity, masculinity, femininity, and nobility are elaborated and proffered’.[29] More than sixty plays featured ‘Turks’, Moors, and Persians in the 1570s to 1603.[30] Marlowe’s thunderous Tamburlaine (c. 1587) in many ways embodies the ‘imperial envy’ that the English exhibited towards the might of central Asia in this period.[31] Tamburlaine’s conquering energies and thirst for slaughter are fuelled by his defeat of the Turkish emperor, who goads him to escalating violence. Plays that staged or referenced Ottomans often related turbans to the unseen but physical presence of circumcision.[32] When the pirate John Ward ‘takes the turban’ in A Christian turn’d Turke, he is also required to undergo circumcision.[33] ‘Ward turn’d Turk? it is not possible’, maintains one pirate, until others offer an eyewitness statement to confirm the finality of the act: ‘I saw him Turk to the Circumcision’.[34]

As the English sought to consolidate their position in the Mediterranean, they came under pressure to engage with Ottomans as commercial and even legal equals. The 1686 articles of peace between England and Algeria declared that if an Englishman ever struck, wounded or murdered a ‘Turke or Moor’ in the ‘Kingdom of Algiers’ they were to ‘be punished in the same manner, and with no greater severity th[a]n a Turk ought to be’.[35] However, not everyone supported growing trade relations with the Ottoman empire. Just as the importation of luxury products from South Asia or the Americas came under attack, so too did coffee, that ‘exotic’ commodity that became popular from the mid-seventeenth-century. Broadsides rebuked the growing trend for drinking coffee in English towns and cities such as London or Oxford. A Broad-side against COFFEE; Or, the Marriage of the Turk (1672) sexualized the consumption of coffee as an act of cultural commingling.[36] The verses describe a marriage between Coffee, a ‘Turkish renegade’, and Christian England, a ‘melting Nymph’, through a series of sexual innuendos and racialized associations that pitch coffee as an assault on English purity: ‘Coffee so brown as berry does appear, / Too swarthy for a Nymph so fair’.[37]

An element of Ottoman life that the English remained largely approving of was that of female submission. The ‘wife of a Turke dare never come where a company of men be gathered together: neither is it lawful for them to go to markets to buy and sell…[in public] There is seldom any speech or conference betwixt men and women’.[38] English writers at times evoked Turkish women to critique the outspokenness and brazenness of women in England.[39] In Philip Massinger’s The Renegado (c. 1630), a North African queen notes that ‘Christian ladies live with much more freedom...our jealous Turks, / Never let their poor wives to be seen’, but prefer them ‘veiled, and guarded’.[40] Modestly-clad Turkish women in veils appeared in drawings and costume books. When Sandys observed during his travels that Ottoman women revealed their beauty only in private, to their families or husbands, he did not cast this in a negative light.[41] Rather, English writers seemed both fascinated by the sexual license of Ottoman men, and largely approving of the submission of Ottoman women.[42] The seraglio of the sultan became, to the English, ‘a proverbial site for sexual excess, sadistic entertainments, and private, pornographic spectacle’, impelling Edgar in King Lear to boast that in women, he had ‘out-paramoured the Turk’.[43]

The figure of the Turk (and the related ‘Mahometan’) in Tudor and Stuart England raised a series of interrelated questions about identity and empire, luxury and political economy. At a time when the English sought to convey their own authority and legitimacy as a Protestant nation in a global context fraught with confessional strife, English writers struggled with the allure and seeming transgressiveness of the Islamic Ottoman world. What Erasmus had deemed the ‘power-lust’ of the Turk was both a cautionary tale and a thing of wonder.[44] Yet much changed between Erasmus’ perception of the Ottomans in the 1520s and one hundred years later, where confessional conflict began to unfold into one of the bloodiest in European history with the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), and again in the later seventeenth century as the English commercial empire expanded. Moreover, more moderate perceptions of Ottoman life circulated alongside the discourses about Turkish might penned by soldiers, prisoners, and playwrights. An album of watercolours from the 1580s, for example, possibly produced in Constantinople by European artists, engaged with the diversity of Ottoman life. The bright illustrations include a view of the Topkapı Palace and ‘A Coffee drinker’ (likely a dervish, or religious man) in a sheepskin cloak, multicoloured cap, and large gold earring.[45] The album labels, in English, offer a sliver of insight into English curiosity about Ottoman life, including coffee-drinking, from an earlier period than might be expected. Commenting on his travels through the Levant in the 1610s, George Sandys recounted how the ‘Saracens and Turks’ who ‘enlarged their Empires, doth at this day well-nigh over-run three parts of the earth; of that I mean that hath civil Inhabitants’.[46] The ‘Turk’ did not just exist in the English imaginary, then, but represented a global reality that the English were increasingly forced to confront, one that was more ‘civil’ than they were at times willing to admit.