On 1 February, the Global History and Culture Centre of the University of Warwick held a workshop on Cross-Cultural Diplomacy Compared: Afro-Eurasian Perspectives (16th-18th Centuries), part of a series of events organized by the Leverhulme Trust funded project Cross-Cultural Diplomacy Compared led by Guido van Meersbergen. Focusing on the diplomatic interactions between Europeans and South Asians, this project aims to expand our understanding of early modern cross-cultural exchanges and develop a truly global perspective on the transcultural dimensions of early modern diplomacy.

The workshop gathered a number of specialists in diplomatic, cultural, and global history to discuss their own work and the recent trends in Global History and New Diplomatic History. Joan-Pau Rubiés surveyed the conceptual and methodological questions surrounding the study of cross-cultural diplomacy and transculturality, proposing an approach that measures cultural distance by exploring diplomatic interactions as a complex process of cultural learning that helped to create a common ground of understanding between agents from different cultural backgrounds. Such an approach requires a careful study of the specific political and economic (and sometimes individual) agenda behind these contacts, as well as the coeval concepts that influenced the perceptions and attitudes of different agents. Rubiés also emphasized the need to develop a model of skeptical calibration based on case-studies in which it is possible to confront both European and local sources. Christine Vogel gave a paper the ritual and performative dimensions of early modern cross-cultural diplomacy. Focusing on her research on European diplomatic interactions with the Ottoman Empire, Vogel proposed the use of semiotic analysis of cross-cultural diplomatic rituals to better understand how the communication and negotiations between agents of different cultural backgrounds emerged.

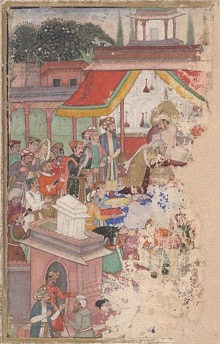

Other papers focused on specific case-studies of cross-cultural diplomacy in West Africa and South Asia. Following his recent comparative studies of the diplomatic practices of the Dutch and English East India Companies in Mughal India, Guido van Meersbergen proposed a typology of six modes of diplomacy based (1) royal embassies, (2) high profile embassies led by company agents, (3) small-scale petitioning at the imperial court, (4) the employment of local brokers, (5) provincial diplomacy and (6) local diplomacy. These different types of diplomatic contacts allow us to better understand how the Dutch and English companies adopted elements from the local diplomatic practices that made them able to operate in the Mughal political landscape. Lennaart Bes presented four examples of protocol breaches in the Dutch interactions with Ikkeri, Madurai, Tanjavur and Ramnad, in order to examine how the diplomatic rituals and etiquette performed at these South Indian courts were used to reinforce, maintain or change relationships. The paper given by Christina Brauner examined the uses of concepts of statehood in the treaties signed between European and African powers noting the existence of a semantic change in the descriptions of African sovereigns and polities which often echoed the early modern European debates on republics and monarchies, the emergence of Orientalism and the profound transformations of the West African political landscape.

The workshop concluded with a roundtable formed by Nandini Das, Zoltán Biedermann and Guido van Meersbergen. The three discussants reviewed the many issues raised throughout the previous panels. Nandini Das opened the debate by arguing that the study of cross-cultural diplomacy should take into account the individual perceptions and emotional reactions of those who participated in cross-cultural interactions. Besides the analysis of personal affective narratives, the cumulative influence of the experiences and memories of diplomatic agents should also be explored with more detail, in order to better understand the connections between diplomatic practices, cultural memories and the movement of people. Another important question that needs to be explored with more attention is the reaction that host societies had to the diplomatic practices brought by Europeans, and the ways in which the host nations also passed through a process of learning and accommodation. Zoltán Biedermann’s intervention underlined the methodological difficulties in identifying and analysis personal feelings in the existing sources. Biedermann also noted that the difficulties faced by most Europeans in imitating or adapting to South Asian diplomatic practices. Such problems reveals that there was a long and complex process of learning specific diplomatic modus operandi, one that mobilized different cultural experiences and political traditions which requires a careful use of concepts such as ‘connected histories’ and ‘mondialisation’. Guido van Meersbergen’s comments highlighted the need to consider the existence of a Eurasian continuum while analyzing the many ways how Europeans developed practices based on Islamic diplomatic culture. The role of prejudices in cross-cultural diplomatic encounters should also be reconsidered, especially when examining the performance of rituals, the exchange of correspondence or the classifications of social and ethnic groups.

The discussions raised by the papers and the roundtable focused around several key aspects of the recent studies on early modern cross-cultural diplomacy, suggesting future paths for research. All the participants pointed out the need to develop comparative studies based on a cross-geographical focus, as well as on the confrontation of different types European and Asian or African sources. The success of such an approach will necessarily require collaborative works joining scholars studying different regions and with varied linguistic skills. Another issued debated throughout the workshop was the importance of understanding the differences between the figure of the ambassador and the practices of diplomacy, which often involved a myriad of other formal and informal agents that played a pivotal role in establishing contacts and negotiations. The discussions also pointed out the need to examine the importance of religion in diplomatic rituals, as well as the role of religious figures as diplomats.

Cross-Cultural Diplomacy Compared was indeed an excellent space for discussion which allowed the authors of the most recent ground-breaking studies in early modern cross-cultural diplomacy to reassess their work and explore future avenues of research.

João Vicente Melo