1 May 2017 marks the five hundredth anniversary of the first documented race riot and greatest outbreak of violence against immigrants in early modern London. Its story is one of anxiety and frustration that was directed as much at the state as it was at the foreigners themselves. In our own climate of fear and insecurity, its themes seem strikingly familiar, but it also inspired one of the most impassioned pleas for the protection of refugees in the English language.

[…contd.]

The May Day riot of 1517 had disclosed a rift within English society. At the time, London’s immigrant community accounted for about 6% of the total population. The English cloth industry in particular offered a ready job market for Flemish and Dutch cloth workers, but there were also affluent communities of French, German, and Italian or ‘Lombard’ merchants who ensured English access both to European markets and trade, and to the crucial continental banking that governed that trade. However, while ostensibly setting the native English against foreigners and immigrants, the 1517 riot was much more fundamentally about widespread frustration among the common people with the state and the Tudor establishment itself. It set poor apprentices and labourers against what they perceived to be the affluent guilds and merchant networks of the city, and it set the city against the court. It fed on rumours of secret negotiations of the powerful, which lined the pockets of the already-rich, both English and foreign, at the cost of the livelihood of the ordinary Englishmen. Even a year earlier, on 28 April 1516, an anonymous bill stuck to the door of St Paul’s had accused the king and his council of financial collusion with foreigners ‘to the undoing of Englishmen’. The riot put both London’s status as a centre of trade and Henry’s own authority as a monarch at risk, and the nature of the uprising meant that the news was likely to circulate all the more widely internationally. It is probably only to be expected that the strength of the response of the authorities was as striking as the lack of preventative action leading up to the event.

In the early hours of May morning, as the rioters started dispersing, the Mayor and his men arrested almost 300 people. Around 5 o’clock in the morning, the king’s forces led by the Duke of Norfolk and others entered the city, and the business of dispensing punishment began. The first trials took place on 4 May. The prisoners were charged not with rioting, but with the much more serious crime of high treason, on the grounds that attacking foreigners both breached the King’s peace within England, and put at risk the peace that Henry had established with all other Christian princes in continental Europe. It is not clear exactly how many men were executed. The two major contemporary historiographers, Edward Hall and the Italian humanist Polydore Vergil, mention 17 and 15 respectively, the Venetian ambassador, Sebastian Justinian mentions 20, while the Papal nuncio or representative, Francesco Chieregato, claimed the much higher figure of 60.

London was still essentially under a 24-hour curfew, with city proclamations specifying that women were to be controlled as strictly as the men, and were not allowed to ‘come together to babble and talk’ (Hall). Over 1300 soldiers brought by the Duke of Norfolk and the Earl of Surrey roamed the streets, and according to Hall, they ‘spake many opprobrious words to the citizens, which grieved them sore’. Hall’s account claims that most of the watermen, priests and servingmen guilty of rioting escaped, and only the ‘poor prentices were taken’, and that some of the boys arrested were little more than children, no more than thirteen years old. Even the account of Polydore Vergil, whose own immigrant status in England understandably made him far more critical of the rioters than Hall, noted in his History of Britain that some who were punished ‘had fallen in with that rabble…more by chance than any deliberation.’ However, Edward Howard, Knight Marshall and youngest son of the Duke of Norfolk ‘showed no mercy, but extreme cruelty to the poor younglings in their execution’. The Mayor and the King’s representatives then arranged to have 11 pairs of gallows to be set up at the main sites of the riot, from Aldgate and Blanchappleton, to Saint Martin’s and Newgate. According to Polydore Vergil, ‘This was a sight unseen in all previous ages, to see so many gallows erected at the same time throughout the city, and it distressed the townsmen’s minds so much that these were removed two weeks later.’ In the meantime, ‘like true subjects’ the people ‘suffered patiently,’ despite easily outnumbering the soldiers (Hall). It was clear that Henry and Wolsey would need to do something quickly to recoup both international prestige and peace in the city.

That political turn began on 7 May, when John Lincoln was brought to court. In his defence, he claimed, ‘My Lords, […] you knew the mischief that is ensued in this realme by strangers, […] many times I have complained, and then I was called a busy fellow: now our lord have mercy on me’. He was executed, but then there was a carefully-engineered dramatic last minute reversal of fortunes. A message of pardon from the king arrived to save the handful of other rioters scheduled to hang after him even as they had ‘the rope about their neckes’, and ‘then the people cried, ‘God save the king’. This was simply a practice-run. On 22 May, Henry followed this with a great public performance of royal power and mercy in the great hall at Westminster, specially hung with tapestry of cloth of gold and decorated with a canopy of brocade for the occasion. This was apparently the result of an intercession by Henry’s wife, Catherine of Aragon, but it is quite likely that the move was masterminded by Wolsey and Henry himself as a way of defusing the standoff between the people and the state. In front of fifteen thousand Londoners, the mayor and representatives of the city, and key courtly figures and lords of the realm, the king and Cardinal Wolsey rebuked both the city and the people for the riot and the danger that it had posed to the King and the state. Then the 400 men and 11 women arrested in the aftermath of the riots were brought in. They had been stripped to their undershirts, and each had a noose around their neck, as if about to be hanged. They threw themselves on their knees, crying for mercy. Cardinal Wolsey and the lords publicly interceded on their behalf, the king appeared moved, and finally relented, but not before more speeches about the rightful duties of citizens had been delivered, and ‘everybody wept for joy’ (Chieregato). Henry and Wolsey had managed to re-engineer the riot against aliens and immigrants into a means of publicly asserting royal power both over the city’s wealthy merchants and guildsmen, and the ordinary labourers, workers and apprentices.

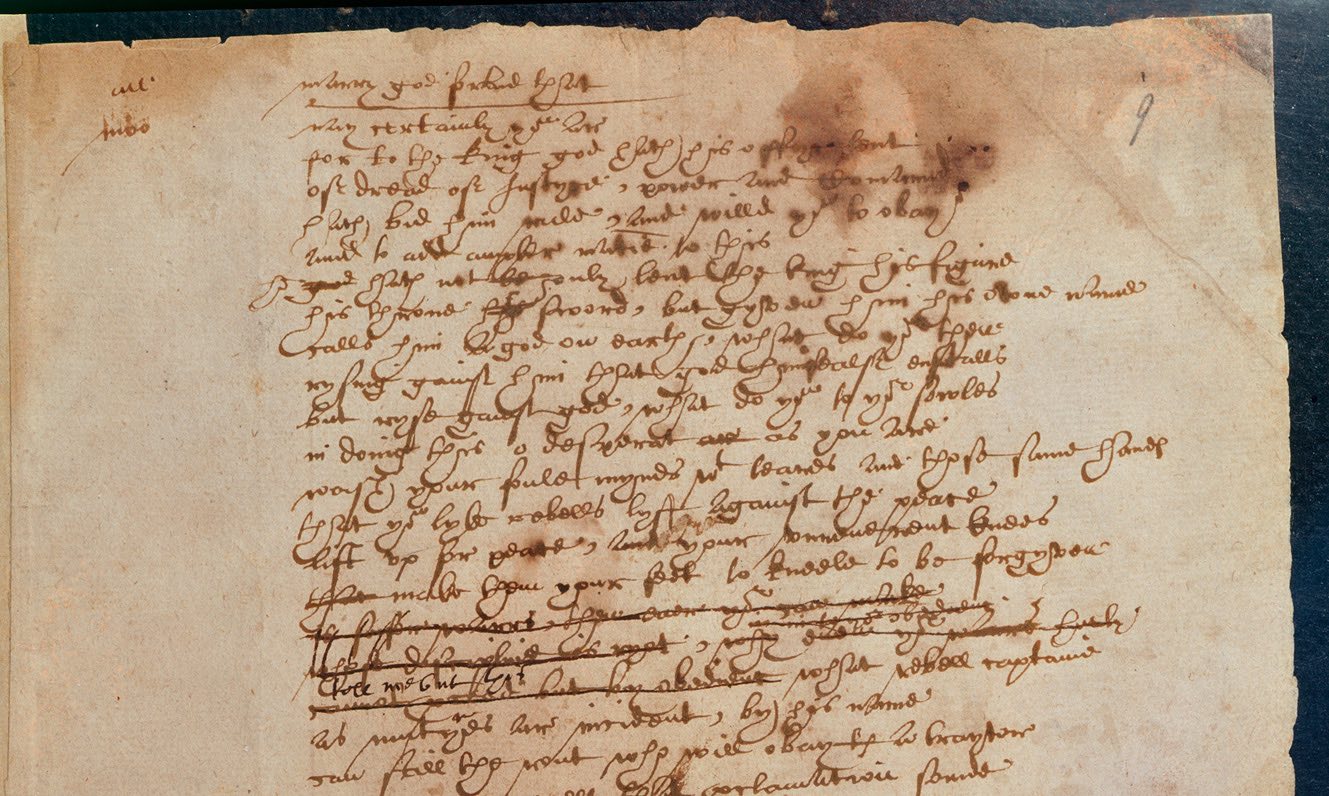

Riots would continue to occur in London from time to time, but the ‘Evil May Day’ of 1517 became notorious, as many historians have pointed out, because such violent outbreaks of resentment against foreigners was an exception in London, not the norm. Years later, however, as waves of Protestant religious refugees from trouble-torn Europe kept seeking shelter in the post-Reformation England of Henry’s daughter, Elizabeth I, radically changing the very nature of its neighbourhoods, and civic unrest became more frequent in the city once more, a group of writers would raise the ghost of that first race riot once again. More’s involvement in the events of the May Day riot forms a substantial part of The Booke of Sir Thomas More, co-written by Anthony Munday and Henry Chettle in the 1590s. Famously, it was criticized by the Master of Revels, Sir Edmund Tilney, who had the power to stop plays from being performed. On the top of the first page of the still-existing manuscript is his hand-written note, ending in what amounts to a thinly-veiled threat: ‘Leave out…the insurrection wholly and the cause thereof, and begin with Sir Thomas More at the Mayor’s sessions, with a report afterwards of his good service done, being Sheriff of London, upon a mutiny against the Lombards – only by a short report and not otherwise, at your own perils.’

Yet the revisions by multiple writers in the manuscript show no sign that his edict was obeyed. And in one of the most substantial additions, a three-page section that is now generally accepted to be in the hand of William Shakespeare, More addresses the rioting mob and invites them – and the audience – to engage in an act of collective empathy. Instead of the poor Englishman railing against the affluent foreigner, ‘Imagine that you see the wretched strangers,’ his More tells the crowd, ‘Their babies at their backs and their poor luggage,/ Plodding to the ports and coasts for transportation,/ And that you sit as kings in your desires […]’. Instead of the foreigner arriving on English shores, he asks them to imagine banishment, spurned like dogs from door to door, ‘like as if that God/ Owed not nor made not you’:

What would you think

To be us’d thus? This is the strangers’ case

And this your mountainish inhumanity.

There is no record to show that The Booke of Sir Thomas More was ever performed, but quite understandably in our current climate of anxiety, More’s speech has gained a new popularity. Its humanity seems fresh and contemporary, its image of the ‘stranger’s case’ uncannily prescient, but perhaps its greatest achievement is one that remains implicit. In its very existence, in its insistence on acting as a mirror in which a harried, troubled, anxious English public sees its own face reflected in the face of a stranger in need, the play claims back the May Day riot from Tudor statecraft, which had tried so hard to turn it simply into an instrument of political maneuvering.

Nandini Das