The objects in our next #gateofaccess series may at first seem a world away from the Tudor portraits or the Italianate neoclassicism that often embody the polished appeal of the Renaissance. Here, we present a defence of the ordinary, where the broken, misshapen things found in rubbish heaps, rather than museum displays, reveal subtle but moving insights into the lives of English individuals. Humanists themselves acknowledged that while a correlation between inner virtue and outer beauty remained the ideal, ‘it is rather good to see a man of body imperfect and disproportioned if he be endued with vertues’. Beautiful bodies with corrupted minds, wrote Lodowick Bryskett in his discussion of civility in 1606, were ‘nought else but a gay vessell filled with vice’.

Working in conjunction with the Museum of Liverpool, this series of objects focuses on the excavations at Rainford in St Helen’s, Merseyside, twelve miles from Liverpool city centre. These objects were excavated by archaeologists and volunteers from National Museums Liverpool and the Merseyside Archaeological Society in 2013, after Sidney Meadows, a local resident, found a seventeenth-century vessel in his garden when digging up a pear tree. Assisted by a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund, this team excavated some 10,000 fragments of pottery and clay pipes in what once served as a kiln dump. Objects from excavations at Bickerstaff, also in Lancashire, are also included here, and reveal the presence of Huguenot glassmakers in local parishes.

The lids, glass, fractured cups and jugs, and colourful pieces of tobacco pipes show the connectedness of local and transatlantic trade, and highlight the influence of continental Europe on production and craft in sixteenth and seventeenth-century England. As our weekly images over the next seven weeks will show, the earthenware display Italian and Germanic styles; glass fragments and parish records testify to the presence of migrant French glassmakers; and attempts at sgraffito suggest a curiosity, or perhaps demand, for Italian techniques in producing clay objects. A Sieburg imitation jug (see image above) resembles the German stoneware so popular in London in the late medieval era, and archaeologists have suggested that potters may have been experimenting with the craft by imitating or adapting the vessels they encountered through popular continental imports. Surviving glass from Bickerstaff indicate the applied furnace decoration typical of the products made by Huguenot glassmakers, many of whom arrived in England from the 1560s, fleeing persecution during a period of devastating confessional strife in France. Tobacco pipes speak to the accelerating appeal of tobacco following increased English activity in the Atlantic from the late sixteenth century, particularly after the establishment of Virginia in 1607. These pipes, in colourful terracotta hues ranging from yellow to green, indicate that although the Pipe Makers’ Company in Westminster held a monopoly on pipe production, local industries used whatever material they had at hand to cash in on an increasingly popular pastime. The particular organic matters of peatland ecosystems made for a specific aesthetic that contrasts to the white Dorset clay pipes used in and around London. All our showcased objects, in fact, offer insight into the convergence between the natural world and man-made things, inviting a consideration of colour schemes and the appearance of domestic interiors as a result of these crafts. Glassware exhibited shades of green created by high levels of iron in the sand used in firing, and the hundreds of coarseware jugs offer a range of hues from dark brown to purple-black. In small, subtle ways, regional firing techniques in artisanal workshops, and the natural resources provided by the peat, moss, coal, and soil in and around Liverpool, offer a way to imagine the aesthetics of the everyday.

These objects hint at broader changes in industry and production, and the role of migration in effecting these changes. They also expose a good deal of law-breaking and questionable morality. The text we show in this series contains the death of a French glassmaker in an entry for December 1600: ‘a stranger slayne by one the glassmen/beinge a frenchman ther workinge’. Profound changes to the glassblowing industry were underway in the Jacobean era, after King James and parliament agreed that using wood for fuel endangered the realm’s forests. Coal, rather than timber, was to be used instead, leading to new firing conditions, and establishing the north as a crucial centre for the realm’s coal production. While the Seiburg imitation jug or French glass demonstrate the influence of Europe on form and technique, the glass and tobacco pipes impel us to face the Atlantic. The Virginia Company made concerted efforts in the 1610s and 1620s to establish glassmaking in Jamestown, where the abundance of timber presented no problems for fuel. The Company employed skilled migrants from Germany and Poland to the colony in 1608, and Italian glassmakers in 1622.

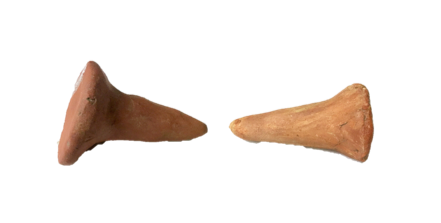

Do small, misshapen objects and mistakes belong in the Renaissance? The answer must be yes. Broken and faulty objects are the humble underbelly of the cultural glory of those Holbeins and Rubens and banqueting halls. They indicate the tireless efforts of craftsmen and artisans as cultural producers. Because the Seiburg jug is ‘a waster, warped and damaged’, it has survived as an example of how, and which, objects were locally produced. Bryskett’s appraisal of human bodies as vessels, and of the possible virtues of imperfection, becomes a fitting way to end as well as begin. The unwieldy clunk of the kiln stilts (below) may have been created purely as props to fire glazed earthenware, but it is because they were never meant to be admired or preserved that they show something remarkable – imprints of the craftsman’s fingers, a reminder of the intimate relationship between people and things, and the power of objects to transmit the past through time.

Lauren Working

Works cited

Lodowick Bryskett, A discourse of civil life (London, 1606; STC 3959).

Sam Rowe and Liz Stewart eds., Rainford’s Roots: The Archaeology of a Village (Liverpool: National Museums Liverpool and Merseyside Archaeological Society, 2014).

Robert Philpott ed., The Pottery and Clay Tobacco Pipe Industries of Rainford, St Helens: New Research (Liverpool: Merseyside Archaeological Society, 2015).