Between 1671 and 1677 John Covel, an Anglican cleric and fellow at Christ’s College, Cambridge, served as chaplain to the English embassy to the court of the Ottoman Empire. During this time, Covel travelled across large parts of Thrace and Asia Minor, before returning to England via much of Greece, Italy and France. Over the course of his travels, Covel devoted a considerable amount of time and energy to studying the Greek Church. This is hardly surprising, given that many Anglicans in this period regarded Greek Christians – because of their geography and history – as witnesses to ancient Christian tradition, who might be relied upon to clarify contentious points of doctrine between – and among – Catholics and Protestants. Covel certainly harnessed his engagement with the Greek Church in this way, using his experiences of Greek worship to intervene in a contemporary dispute among English divines over the use of the sign of the cross, particularly in baptism, where it was commonly performed over the forehead of the baptised.

In the second half of the seventeenth century, English Protestants were divided over whether the sign of the cross was a fundamental Christian behaviour, or simply a superstitious rite which had developed out of the Roman corruption of the faith in the Middle Ages. For the Presbyterian minister Richard Baxter (1615-91), the sign of the cross was ‘a (transient) Image, used as a means of Worship’, and ‘Therefore unlawful by the Second Commandment.’[1] Covel was of a completely different mind, however, owing partly to his encounter with the Greek Church in the Ottoman Empire, which had taught him the value of the practice.[2] In his correspondence, Covel related a story about ‘a poor Greek’ sentenced to death by the Ottoman authorities, whom he watched during his trial and execution, noting that:

when either he could not speak, through weaknesse of body or anguish of mind or else could not be heard amongst the thronging multitude, he in a manner continually made the sign of the crosse upon his breast, to signify to the world by this dumb Rhetorick his undaunted resolution of being and dying a true Christian. I confesse it made me wth great pleasure reflect upon that antient Rite used by our church in Baptisme, I mean ye sign of the Crosse.

Covel’s description here of the sign of the cross as ‘that antient Rite used by our Church in Baptisme’ was significant in and of itself, for it pre-empted the common criticism that it was merely a Medieval Catholic invention, without precedent in the early Church. In any case, Covel conceded that the sign of the cross ‘may seem a very uselesse and empty ceremony’, whether in baptism or among adult Christians, ‘to men that never lived abroad amongst unbelievers, nor considered the state of the primitive Church by which this practice prevayled’. Yet of course Covel, unlike most of his compatriots and colleagues, had ‘lived abroad amongst unbelievers’, where he had witnessed the persecution of Christians at the hands of the non-Christian Ottomans, which provided him with a different perspective on the sign of the cross. For under these circumstances, Covel had found the practice very useful, for it signified ‘throughout the whole world, where no other language is understood, that the person so signed is own’d, or owns himself to be a member of Christ’s body.’ By way of illustration, Covel informed the recipient of his letter that in Ottoman territories, the sign was commonly used by local Christians to ‘begge your charity, when all language is insignificant’. Covel also recalled using the sign himself, when he had travelled ‘in Turkish habit [or dress]’, in order to reassure frightened local Christians that he was of their faith, and thereby ensure that he was ‘immediately admitted and kindly treated’ by them.

Covel had therefore seen what it must have been like for those early generations of ‘primitive’ Christians, surrounded by ‘unbelievers’ and subjected to frequent bouts of persecution. Although English Christians no longer faced such challenges, the sign of the cross, even if used only in baptism, remained a potent symbol of Christian solidarity, of one’s resolution to ‘maintein the inward and spirituall fight against sin and the Devil’, and a crucial reminder that Christians, wherever they found themselves, ‘should not be ashamed publickly, even by this outward sign, to confesse to ye world and all the powers’ their faith in Jesus Christ. In Covel’s view, the sign of the cross was part of the ‘universal Character of a Christian, which was wisely introduced by our forefathers and ought still to be used’, particularly in baptism.

Thus Covel believed that his direct experience of a Church persecuted by non-Christians gave him unique insight, noting, as we have seen, that the sign of the cross only appeared useless to those ‘that never lived abroad amongst unbelievers’. In using the Greek Church to defend the practice, Covel distinguished himself from several of his Anglican colleagues, who championed the sign of the cross using the writings of theologians from the early Church. In so doing, Covel suggested that overseas travel, and exposure to religious diversity specifically, equipped one with a better sense of right belief and devotion, particularly when it came to contested issues such as the sign of the cross. Indeed, Covel’s defence of the sign of the cross vis-à-vis the Greek Church testifies to the role of early modern travel, and of transcultural exposure, in shaping and shifting travellers’ views of familiar debates at home, in ways that often distinguished them from their non-travelling contemporaries.

Fig. 1: Portrait of John Covel, c. 1716. Painted by Claude Laudius Guynier (fl. 1713-16), oil on canvas. Available via Wikimedia Commons.

Fig. 1: Portrait of John Covel, c. 1716. Painted by Claude Laudius Guynier (fl. 1713-16), oil on canvas. Available via Wikimedia Commons.

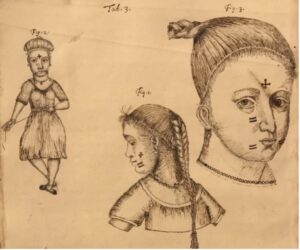

Fig. 2: Covel’s sketches of Bedouin women in North Africa, whose faces were inked with crosses, though they had long since converted from Christianity to Islam. See British Library (hence BL), Add. MS 22912, 27v.

Fig. 2: Covel’s sketches of Bedouin women in North Africa, whose faces were inked with crosses, though they had long since converted from Christianity to Islam. See British Library (hence BL), Add. MS 22912, 27v.

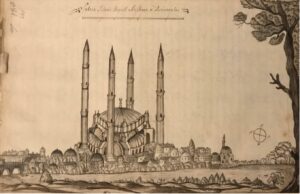

Fig. 3: ‘Sultan Selym’s Royall Mosque in Adrianople’, drawn by the French artist Jerome Saltier, whom Covel met in Izmir. See BL, Add. MS 22912, 231r.[3]

Fig. 3: ‘Sultan Selym’s Royall Mosque in Adrianople’, drawn by the French artist Jerome Saltier, whom Covel met in Izmir. See BL, Add. MS 22912, 231r.[3]

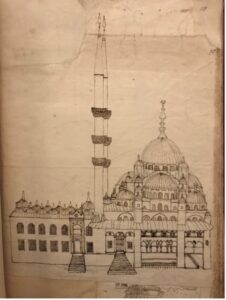

Fig. 4: Covel’s sketch of the New Valide Mosque in Istanbul. See BL, Add. MS 22912, 118r.

Fig. 4: Covel’s sketch of the New Valide Mosque in Istanbul. See BL, Add. MS 22912, 118r.

[2] Covel’s remarks about the sign of the cross are quoted from John Covel, ‘A peice of my letter to Dr Womock about ye Crosse in baptisme’, date unknown, London, BL, Add. MS 22910, 115.

[3] See also Jean-Pierre Grélois, ed., Dr John Covel, Voyages En Turquie 1675-1677. Texte Anglais Établie, Annoté et Traduit Par Jean-Pierre Grélois (Paris: P. Lethielleux, 1998), 108–9.

Charles Beirouti

University of Oxford

charles.beirouti@new.ox.ac.uk

Biography

Funded jointly by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and New College, my research centres broadly on the depiction of religious diversity in seventeenth-century English and French travel accounts, particularly those written by clerics who lived, worked and travelled in the Islamic world, stretching from the eastern Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. My broader research interests include seventeenth-century European travel and travel literature; Europe’s relations with and perceptions of the Islamic world from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment; seventeenth- and eighteenth-century British and French history, particularly religious and intellectual; the practice of Islam in the seventeenth-century Islamic world, particularly in the Mughal and Ottoman empires; and non-Muslim communities in seventeenth-century Islamic states, particularly Eastern Christians.