I have been trying to trace an elusive figure over the last couple of months. When the libraries closed, I thought it would be a good idea to let my search rest for a while. For reasons that are not entirely clear to myself, I had a vague idea of sneaking up on my unsuspecting object of study in the crammed manuscript pages of archival documents once we were allowed to venture out again. The problem is that I keep spotting tantalising references – like a figure glimpsed out of the corner of the eye – before the traces disappear again.

The figure in question is a man, an Indian broker retained by the fledgling East India Company in the early 1600s, at a time when the English were still trying to figure out the nature of their ‘enterprise’ in South Asia. The records refer to him variously as Jadu, Jadow, or even, in one case, ‘Sadow,’ and there are quite a few records to go through. His is the one Indian name that crops up time and again in the correspondence of the English merchants trying to establish a toehold in Surat, the first English ambassador attempting to decipher the diplomatic practices of the Mughal court, and the Company in London, measuring success and loss in their accounts.

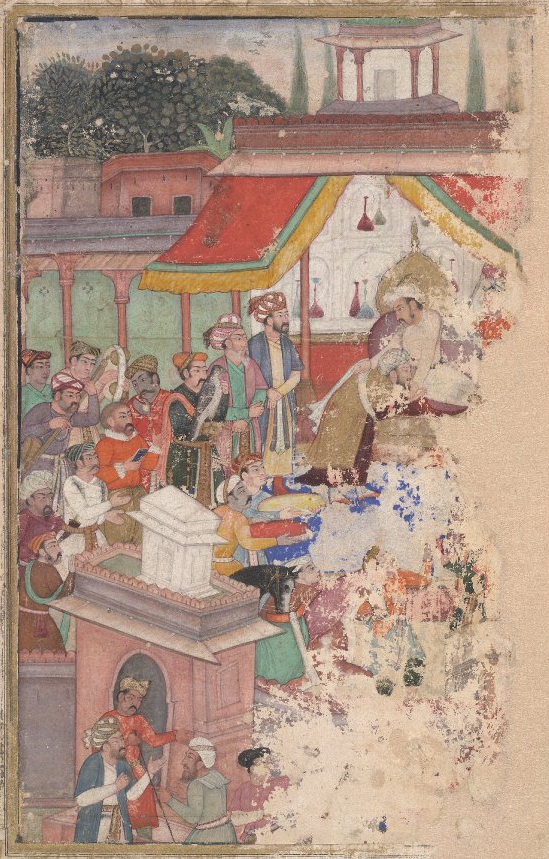

It seems that Jadu was one of the first Indian brokers to the East India Company. There is a reference to him helping the EIC merchant, John Jourdain, escape Portuguese blockades and board an English ship in 1611.[1] In 1616, the ambassador, Sir Thomas Roe, lasts exactly 5 days when Jadu leaves his service over a disagreement about his wages. ‘I am so without any linguist that I cannot answer the King what it were a clock,’ Roe complains, and sends messengers after him to call him back: cue much relief in Roe’s meticulous journal when Jadu reports for duty on Christmas Eve, 1616, and a new contract is agreed.[2]

It seems that Jadu was one of the first Indian brokers to the East India Company. There is a reference to him helping the EIC merchant, John Jourdain, escape Portuguese blockades and board an English ship in 1611. In 1616, the ambassador, Sir Thomas Roe, lasts exactly 5 days when Jadu leaves his service over a disagreement about his wages. ‘I am so without any linguist that I cannot answer the King what it were a clock,’ Roe complains, and sends messengers after him to call him back: cue much relief in Roe’s meticulous journal when Jadu reports for duty on Christmas Eve, 1616, and a new contract is agreed.

Trying to trace Jadu is firstly an exercise in decoding the various products of phonetic mangling of Indian names in English accounts. There is a marked ambivalence about him throughout that act as a connecting thread among all those appearances. There is uncertainty about his trustworthiness as a financial and mercantile intermediary, coupled with uncertainty about language. Jadu translates for Thomas Roe, who – despite a relatively long sojourn in India (1615-19), is remarkably resistant to acquiring any Indian languages himself. The problem is that he never quite appears to trust the exchanges that Jadu facilitates with Mughal court officials either. That ambivalence is familiar: as we revised the entry for ‘agent/broker’ in TIDE: Keywords over the last few months, we were reminded time and again of the shifting sands on which such intermediaries operated. Their ability to move between languages, as well as within multiple networks made them both indispensable, and the subject of suspicion and mistrust.

But my attempts to trace Jadu also reaffirm the difficulties that attend our efforts to trace non-European presence and agency on which European endeavours so often depended. Jadu continues to elude me. He remains a shadowy figure behind the financial, mercantile, and social dealings of the English in India for over two decades – then disappears without a trace. In the only scholarly article about him, Amrita Sen notes that ‘Jadu’, a name derived from the Hindu god Vishnu, was and is still common in India, and that he may have been ’a member of what could be considered the indigenous elite—the Surat Banians.’[3] He is likely to have had a wife, or a ‘woman,’ as one English account puts it in 1609.[4] Elsewhere, in EIC records, I find repeated references to his connections within the Surat bania community – he comes from a family of prominent brokers variously employed by foreign merchants. Company records refer to him as 'Jadowe, the kinsman of Gourdas, and of Calliangee [Kalyanji]'.[5] He is repeatedly accused of ‘cozening’ Company merchants, fined or otherwise reprimanded, then brought back, and the remarkable profit margins in Company trade deals often note his involvement in the negotiations. The last reference I could find of him, dated 1635, is typically short and fleeting. It simply notes the hopelessness of ‘recovering any money from Jadu, who is very poor’.[6]

Nandini Das

- 1.The Journal of John Jourdain, 1608-1617, ed. William Foster (London, 1905), p. 178.

- 2.The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to India, ed. William Foster (London, 1926), pp.326-29.

- 3. Amrita Sen, ‘Searching for the Indian in the English East India Company Archives: The Case of Jadow the Broker and Early Seventeenth-Century Anglo-Mughal Trade,’ Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies, 17.3 (2017), pp. 37-58.

- 4. Danvers, Frederick Charles, ed. Letters Received by the East India Company from its Servants in the East Transcribed from the ‘Original Correspondence’ Series of the India Office Records. Vol. I. 1602–1613 (London, 1896), pp. 26.

- 5.The English factories in India (1630-1633), ed. Foster (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1910), p. 90.

- The English factories in India (1630-1633), p. 275.