It's a delight and honour to introduce this blog post by Sara Pelham on our work, and our recent theatre workshop at the University of Oxford. This workshop was part of our consultancy with ERC TIDE, which explored the links between Emma Frankland’s upcoming production of John Lyly’s Galatea and TIDE’s project research into travel and identity in early modern England. Galatea is an extraordinarily important early modern English play, and yet the play has almost no stage history since 1588, and is only starting to be better known amongst academics and students. The play offers contemporary performers and audiences an unparalleled affirmative and intersectional demographic, exploring feminist, queer, transgender and migrant lives in a cast of characters that includes very few cisgender adult males, and builds towards the celebration of a queer and trans marriage. Emma Frankland, Andy Kesson, and a group of performers and researchers have developed a production of Galatea which foregrounds the role of migrants and migration in the play, and which aims to centre intersectional identities of all kinds. Galatea will be staged in May 2023 in the UK – we aren't allowed to be more specific yet, but keep an eye out for our show!

Dr Andy Kesson

An Afternoon with Galatea:

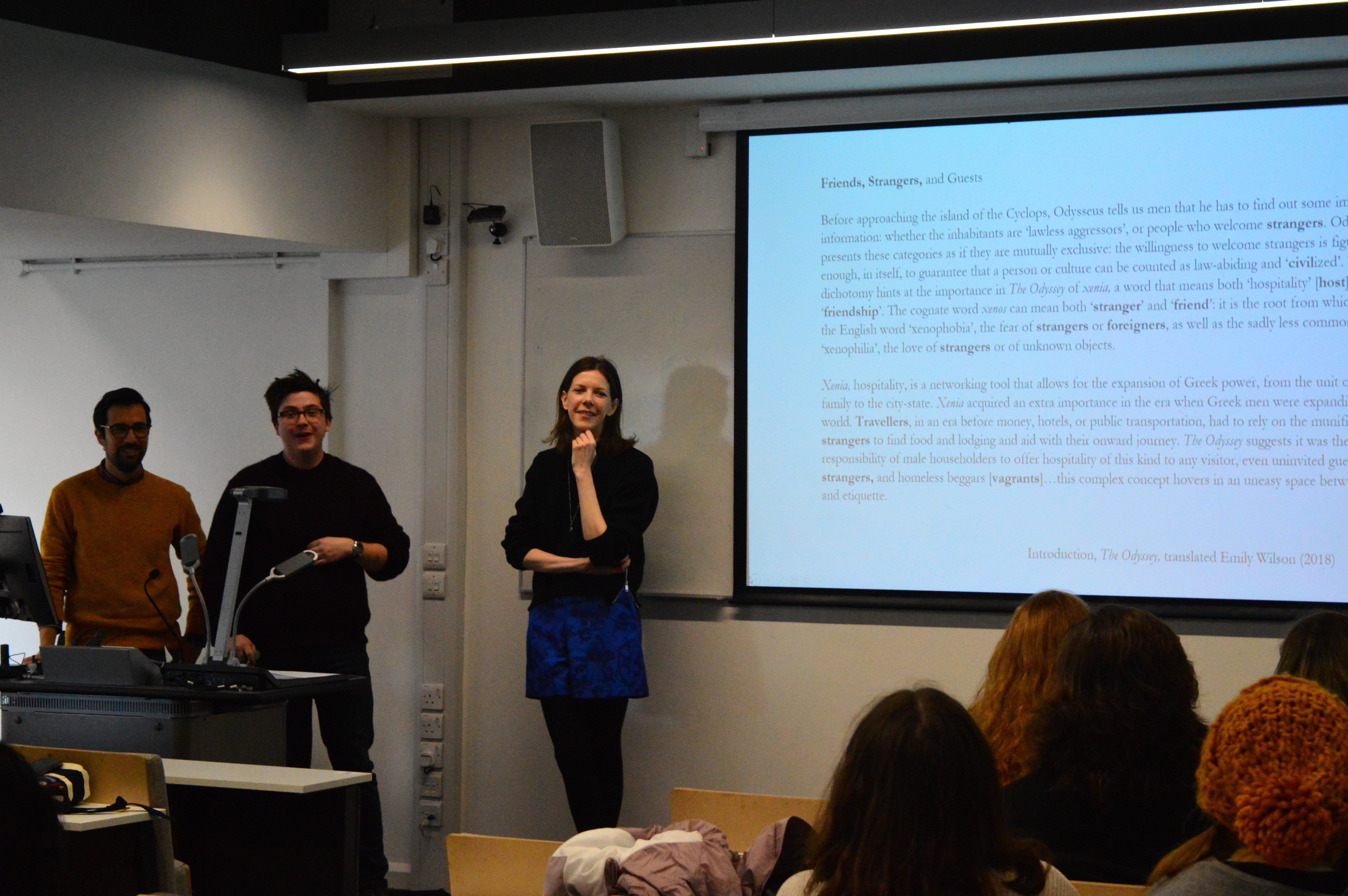

In the stuffy, tiered lecture room 2 of the English Faculty building in Oxford, Emma Frankland, Andy Kesson and Subira Joy introduced us to their work on their upcoming production of John Lyly's early modern play and queer love story, Galatea.

Exploring an early modern playwright other than Shakespeare was an enlightening experience. Unlike Shakespeare, Lyly wasn’t dedicated two entire mandatory terms of study in Oxford’s English literature degree. As we spent the afternoon engaging with Galatea some beliefs of mine were confirmed: that the early modern period is not just Shakespeare, and that we should perhaps take him off his pedestal!

Binary gender roles and patriarchal customs are commonly found in Shakespeare’s works and wider canonical narratives; and even in instances where early modern social expectations are challenged and resisted (like the notable crossdressing in Twelfth Night and As You Like It), these seemingly transgressive plays still conclude with cis-het-normative rectifications.

As a story that reveals the euphoric effects of crossdressing, deposits Neptune of from his position of patriarchal control, and ends with the divine approval of a queer union, Lyly’s Galatea, however, is a work that is feminist, accepting of queer love, and promoting trans joy.

The play’s queerness extends beyond its surface-level subversion of normative sexuality, gender identity and gender roles, and plays out more implicitly in its fluid setting. Even at the most fundamental, pragmatic level, binaries and boundaries collapse when we find out that the play was staged for a woman (Elizabeth I) and performed on a stage owned by a woman (Blackfriars). Everything about this work breaks contemporaneous conventions and Lyly has Venus clearly affirm in response, “I like well, and allow it.”

Revived for the first time since it was last known to be performed 500 years ago, Emma Frankland’s Galatea takes Lyly’s queer legacy and uses it to open up silenced narratives and uplift marginalised voices. She allows for an open-ended exploration of identity by applying the lived identities and experiences of her actors to the performance. She invites them to share elements of themselves in the project, instead of reducing their roles to a single category as happens in much mainstream theatre.

The production has unfortunately been in working progress for the past six years due to a lack of funding. What this delayed production has allowed, however, is an extensive exploration and sensitive understanding such dense aspects of identity truly deserve. During the workshop, Emma Frankland talked of how such time really allowed for the “undoing of each other’s gender” and the grappling with the play’s “gender confusion”. Questions like, “Is Galatea trans masc?” or “Philida doesn’t like wearing the masc clothes and Galatea does, does this make Philida trans fem?” were raised along the way. Initially a result of invalidation, the prolonged time it has taken to shape the project has opened up a positive space to explore identity in all its complexities and free the performance from rigid social expectations. It shows how stories are ever-expanding and can be pushed to encompass marginalised-inclusive spaces that were previously never made, let alone thought, possible.

This expansiveness was really felt in the lecture room itself. When Emma, Andy and Subira first entered lecture room 2 room, it was clear that the space was not ideal. It immediately created a divide between us and them. Emma pointed out that the set up was somewhat “hierarchical”. But they encouraged us to creatively acclimatize to it and this made me come to a lovely realisation: that queer people, who’ve been handed a cis-het-normative world, will find ways to make this space our own and claim our place in it. We will constantly make use of what we’re given, and make it better.

What also notably helped understand the space and discover its malleability was Andy Kesson’s suggested improv status game. The space was not ideal, but, with some roaming around the room of our own and some awful attempts at acting, I found that the game, in the given space, began to make more sense as it allowed for questions of agency (with its relation to status) to be explored.

Even with this short activity alone, the familiarity of the English lecture room – where hours of labouring lectures on the greats and the classics had been delivered to me – was beginning to break down. Our creative adaptation to the space we were given helped destabilise our rigid cognitive ways so that new understandings about status could arise.

My understandings of the Early Modern period and Shakespeare in particular were challenged upon hearing Emma’s, Andy’s and Subira’s thoughts on Lyly. Unlike the archaic ways of the past, Lyly’s work is very much in line with openness and acceptance of identity in the present. The workshop demonstrated how Shakespeare doesn’t have a story for everyone, and this is a notion that, as Emma declared, is “important to break down.”. Shakespeare isn’t the ‘universal voice’ he is often made out to be.

Within these few hours of the afternoon, I really felt Oxford’s academic tradition re-forming into something new, I felt my interests in works beyond the classics and the greats being validated, and most invigorating of all, I felt my identity, as a queer person in the arts, being affirmed. Such an afternoon is a rare find, which goes to show that the university still has so much work to do to make sure that these spaces remain open, and these conversations continue.

Sara Pelham

English and French

Exeter College, Oxford

Pearls and Empire

Prompted by our reading of the 1592 account of the English capture of the Portuguese ship, the Madre De Dios, published in Richard Hakluyt’s The Principal Navigations (1599), we were fascinated by the range of objects listed in the account, and chose to research more about the circulation of pearls. It was important for us that we think about the dangerous labour and production that underpinned the pearl trade, and not just their associations with beauty and luxury in European literature and art.

Figure 1. Standing Ram Pendant, British Museum, donated by Ferdinand Anselm Rothschild. The above pendant from the British Museum is believed to have been made in Spain during the 1500s with pearls sourced from South America.

Figure 1. Standing Ram Pendant, British Museum, donated by Ferdinand Anselm Rothschild. The above pendant from the British Museum is believed to have been made in Spain during the 1500s with pearls sourced from South America.

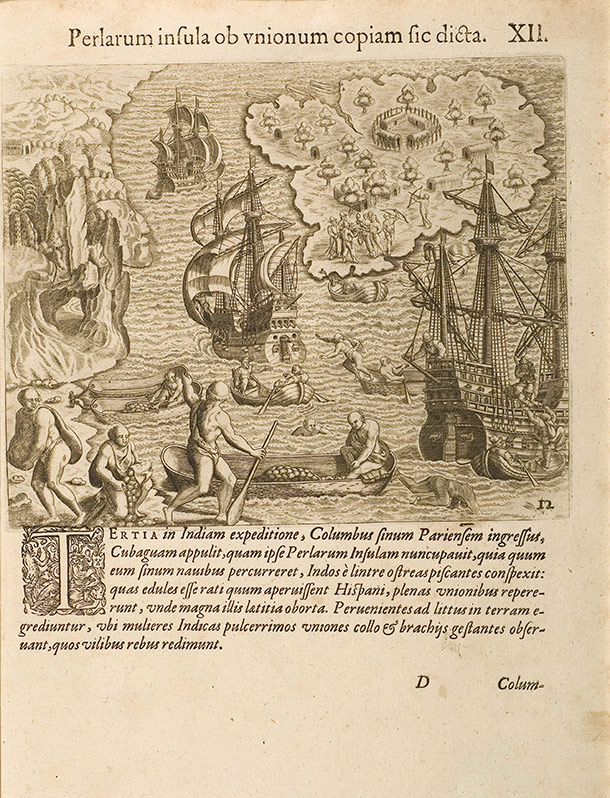

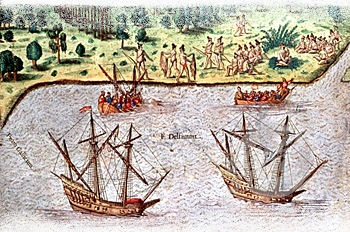

Figure 2. Pearl fishing in the Caribbean, from Les Grands Voyages (1590).

Figure 2. Pearl fishing in the Caribbean, from Les Grands Voyages (1590).

Figure 3: Illustration of the Koh-i-Noor on display at the Great Exhibition, featured in Illustrated London News (1851). Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Figure 3: Illustration of the Koh-i-Noor on display at the Great Exhibition, featured in Illustrated London News (1851). Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Grace Dye

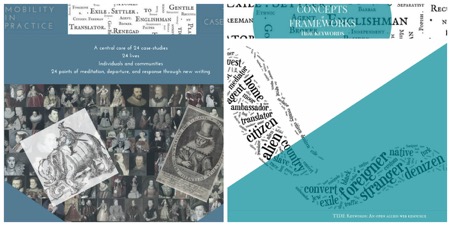

In my first semester as a new assistant professor at Butler University, I incorporated ERC-TIDE’s open-access Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern England (Amsterdam UP, 2021) in my undergraduate British Literature survey on worlding and worldmaking. In the text we read, my class traced how British writers of the premodern past imagined the world and their place in it. To this end, our class was interested in how language contributes to world-building: particularly, how words shape our knowledge of the world, our encounter with difference, and our understanding of the expansive scope of space and time. Looking through the interpretive prism of TIDE’s Keywords, my students quickly realized that language points to conceptions of the world in two different directions: one aims at possession, control, and extraction, or what postcolonial theorists like Gayatri Spivak call “worlding”; and the other, worldmaking, especially when attached to marginalized communities, dreams of alternative worlds built around human and planetary interconnectedness or conviviality (see the scholarship of Paul Gilroy and Pheng Cheah).

The historical essay assignment builds on Amrita Dhar’s incisive and generative lesson prompts, which she details in a post on this website’s blog. In the spirit of circulating rather than hoarding knowledge, students chose a keyword each; they wrote about their keyword’s journey from the premodern past into our present; and most importantly, they shared the insight they harvested during lively class presentations. By emphasizing collaborative learning, this assignment provided a daily reminder that language and power are intimately connected; they exist as facets of the same apparatus through which we can detect the workings of empire and its mechanisms of racial terror. For example, the conversations around the keywords “rogue,” “vagrant,” “alien/stranger,” and “gypsy” offered a glimpse of a world defined against belonging and in relation to citizenry, surveillance, and control. Asking students to position their keyword in the context of worlding and worldmaking allowed them to draw informed conclusions about the constellations of material and figurative forces that survey and hierarchize the world we continue to inhabit.

Closer to home, words shape policy, justify war, and have consequences on real lives. To illustrate my point, I will focus on the keyword “rogue”; particularly, how my class’s discussion of this keyword opened up critical paths to explore the power dynamics that render a person, groups, or nations as threatening outsiders, in the premodern past as well as in our lived realities. In the “Act for Punishment of Vagabonds” (1572), my class detected the punitive language of the state in eradicating those who threaten its ideology. When we juxtaposed “rogue” with the keyword “citizen,” we discerned the rhetorical strategies that inversely authorize the ideal citizen from which these borderless people depart. More perniciously, this language hardens through time: what starts as policing “lawless” individuals in the premodern past morphs into the hegemonic control of “rogue states” in our present.

The word “rogue,” my class realized, was utilized to designate nation-states that did not adhere to the Western hegemonic world order. The same rhetorical strategies that legitimized the identification and persecution of outsiders in the premodern past, including vagrants and vagabonds, the poor and the homeless, seasonal workers and refugees, migrated into our twenty-first-century world. In United States foreign policy lexicon, the word “rogue” became a nomenclature for recalcitrant and racialized states such as Iraq, Iran, Cuba, and Libya, “whose identity is to some extent defined by acting outside of the standard rules of international law,” in the words of Former National Security Advisor Anthony Lake. This “rogue” designation justified aggressive intervention, from economic sanctions, to regime change, to violent bombing campaigns.

Undoubtedly, my students were amenable to making connections through a transhistorical arc because they have digested the main purpose of Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility: “to examine certain terms which repeatedly illuminated points of tension, debate, and change around issues of identity, race, and belonging throughout this period” (9). What this work makes crystal clear is that as present-day readers of the humanities, we cannot overlook, excuse, and rationalize histories of violence. As residents of an imperialist power on stolen indigenous land, one that continues to punish homeless and migrant people, criminalize borders, and violate the Global South, our duty is to address, to make legible, the attendant harm in the texts we read, as we dream of a just and harmonious future.

Mira Assaf Kafantaris

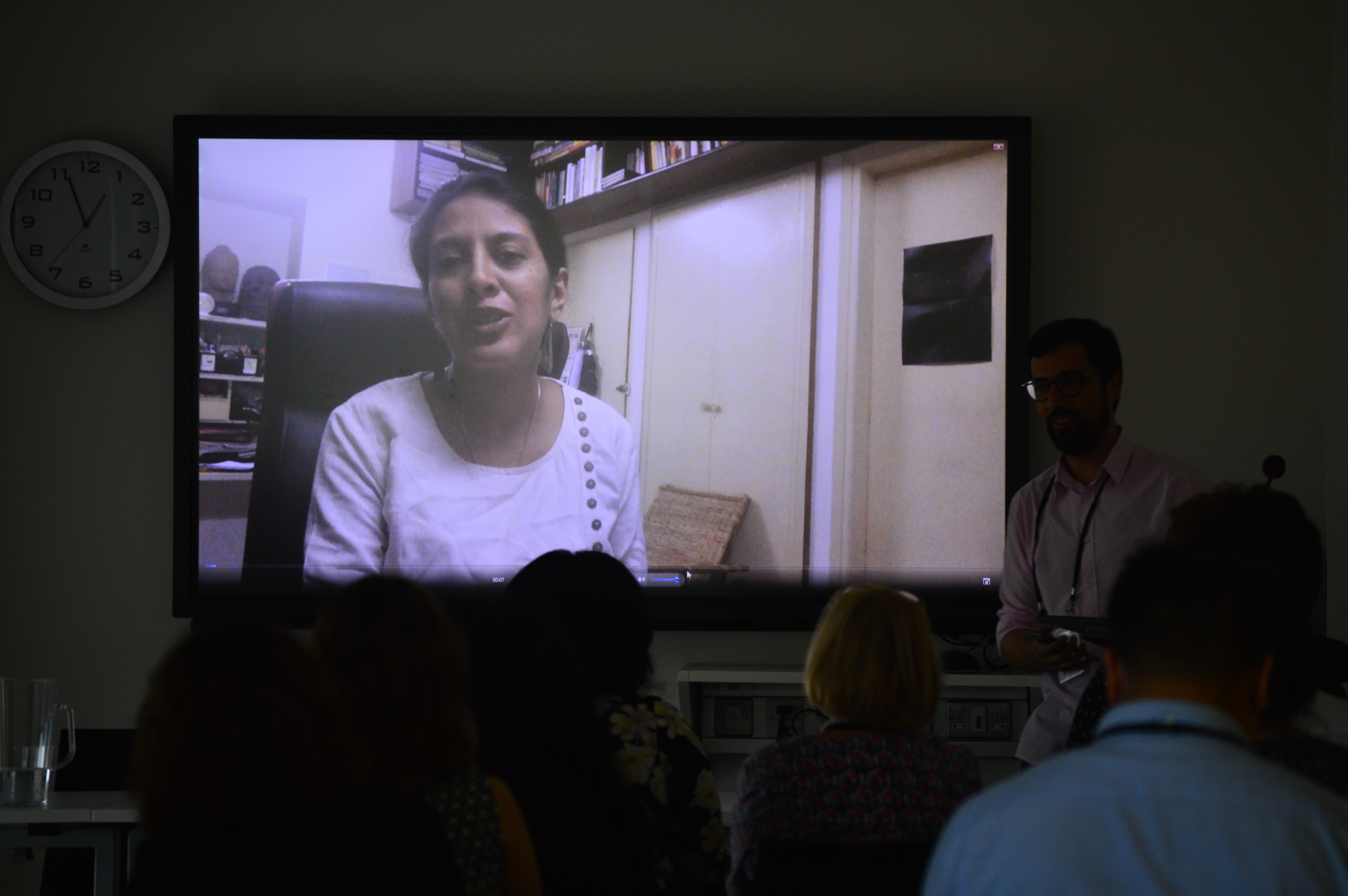

On the weekend of 31 July and 1 August 2021, following its ‘On Belonging’ conference, TIDE held a free online cultural festival. Through seven events, TIDEfest showcased the project’s five-year engagement with creative practitioners, bringing together all of TIDE’s visiting writers and a range of other authors, educators, and artists.

TIDEfest began with ‘Teaching Migration, Empire, and Belonging in Schools’ with writer Nikesh Shukla, historian Kate Williams, and teachers and researchers, Wendy Lennon and Hannah Cusworth. In the afternoon, Preti Taneja discussed her award-winning novel, We That Are Young, and shared the writing she had produced for the interactive multimedia collaboration, TIDE Salon. Written from the future, Preti’s ‘fragments’ powerfully layer places and time, where the era of social media and digital fragments share space with Sappho and dark matter, Montaigne and a new millennium. An archive, Preti reminds us, ‘is whatever falls into an envelope’. ‘Giving Voice Part 1’ was a creative writing workshop led by the award-winning poets Sarah Howe and Fred D’Aguiar, where participants were guided through a series of writing exercises that drew on objects, from a carved ivory salt cellar to Chinese porcelain, introduced by curators from the London National Portrait Gallery, Pitt Rivers Museum, World Museum, and Oxford Herbaria. The day concluded with Nikesh Shukla in conversation with the authors Yashica Dutt and Tanaïs, who discussed writing memoir, generational trauma, and ‘bringing truth to the page’. Throughout the day, there were multiple discussions about the destruction of archives, from Windrush records to Hindu temples, and about the responsibility scholars have to recover the fragments of the past. Writers also expressed the importance of making visible these processes of recuperation and to acknowledge the biases and ‘curatorial silences’ that might arise. This echoed Ladan Niayesh’s evocative reference in her paper for the ‘On Belonging’ conference a few days before: as with the rebuilding of Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral after the 2019 fires, historians looking at the materials of the past must continually ask themselves what aspects of history to interpret, restore, make visible, and preserve.

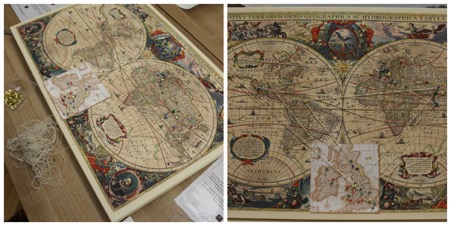

The second day of TIDEfest began with ‘Globes, Networks, & the Early Modern World’, an event featuring TIDE postdoctoral researchers Lauren Working and Emily Stevenson and the artist Loraine Rutt. The three discussed their forthcoming collaborative exhibition, ‘From the Middle Temple to Manoa’, organised with Middle Temple librarian Renae Satterley and forthcoming at Middle Temple Library in London in autumn 2021. Their discussion moved from early modern travel and contemporary globemaking to digital social network analysis, examining ways of bringing these different areas of exploration into conversation and effective collaboration. This event was followed by a reading by TIDE’s current visiting writer Elif Shafak from her new book, The Island of Missing Trees, and a conversation between Elif and Nandini Das about family memory, democratic rights, and how a book that adopts the perspective of a tree can invite us to step outside of our human perspectives. TIDEfest concluded with ‘Giving Voice Part 2’ with poets Sarah Howe, Fred D’Aguiar, and Sandeep Parmar. This final event saw the premiere of two film poems based on Fred and Sarah’s TIDE-commissioned poetry, and featured a discussion of the many poems submitted online as part of Sarah and Fred’s workshop the day before (you can read some of these on Twitter by following the hashtag #SpeakingObjects). ‘Giving Voice’ also unveiled a poem jointly written by Fred and Sarah as their own response to the workshop prompts. Fred, Sarah, and Sandeep spoke powerfully about the urgency of dialogue, excavation, and the need for writers and academics to work together to make sense of the present as well as the past. In the words of Fred D’Aguiar: ‘history is a scary place. I’m not going in there alone’. Celebrating collaboration and collective effort, it was the perfect way to bring TIDEfest, and the preceding ‘On Belonging’ conference, to a close, with a reminder that belonging and identity are rarely singular concepts; they exist as layers and intersections moving across borders, meaning different things in different places.

Lauren Working and Emily Stevenson

Almost exactly three years after our first ‘On Belonging’ conference, the TIDE team organised a digital follow-up to expand on and reflect upon the conversations we have had so far. Though COVID-19 restrictions took us online, running a virtual event also offered a number of benefits. We were able to offer a longer, much more expansive conference than before, and also trial several new initiatives to help make academic conferencing more inclusive, accessible, and communal. Spanning 5 days, ‘On Belonging 2: English Conceptions of Migration and Transculturality, 1550-1700’ included 2 social events, 15 panels, 3 roundtables, and 1 book launch, totalling 66 papers, presentations, roundtables, and creative sessions that amounted to 24 hours’ worth of digital content. Forgoing the traditional keynotes meant that each voice had an equal weight in these discussions of belonging, identity, migration, and race regardless of career stage. Pre-recording the sessions and making them available on YouTube and Crowdcast for preview and catch-up recognised the time restrictions of our different work and personal commitments, giving attendees the opportunity to engage in these conversations at a time of their convenience. For those who could not attend ‘On Belonging 2’ at all, proceedings were live-tweeted from the TIDE account across the week. In total, the account tweeted 500 times during the course of the conference, resulting in 114 new followers and over 24,000 profile visits. Without costly and time-consuming international travel, we were able to bring academics from Seoul and the US in conversation with academics in Oxford, and provide ECRs from Germany, India, and elsewhere with a platform to discuss their ideas on border crossing and borders crossers. In total, the conference’s innovative digital platform successfully brought together 66 scholars across six continents. The low running costs also allowed TIDE to offer attendance to all free of charge. In lieu of a fee, participants and attendees in full-time employment were instead encouraged to donate a discretionary amount to the Society of Renaissance Studies (SRS) in order to help fund their ECR and inclusivity initiatives – an innovative addition to registration that has helped set the template for how the SRS offers financial support.

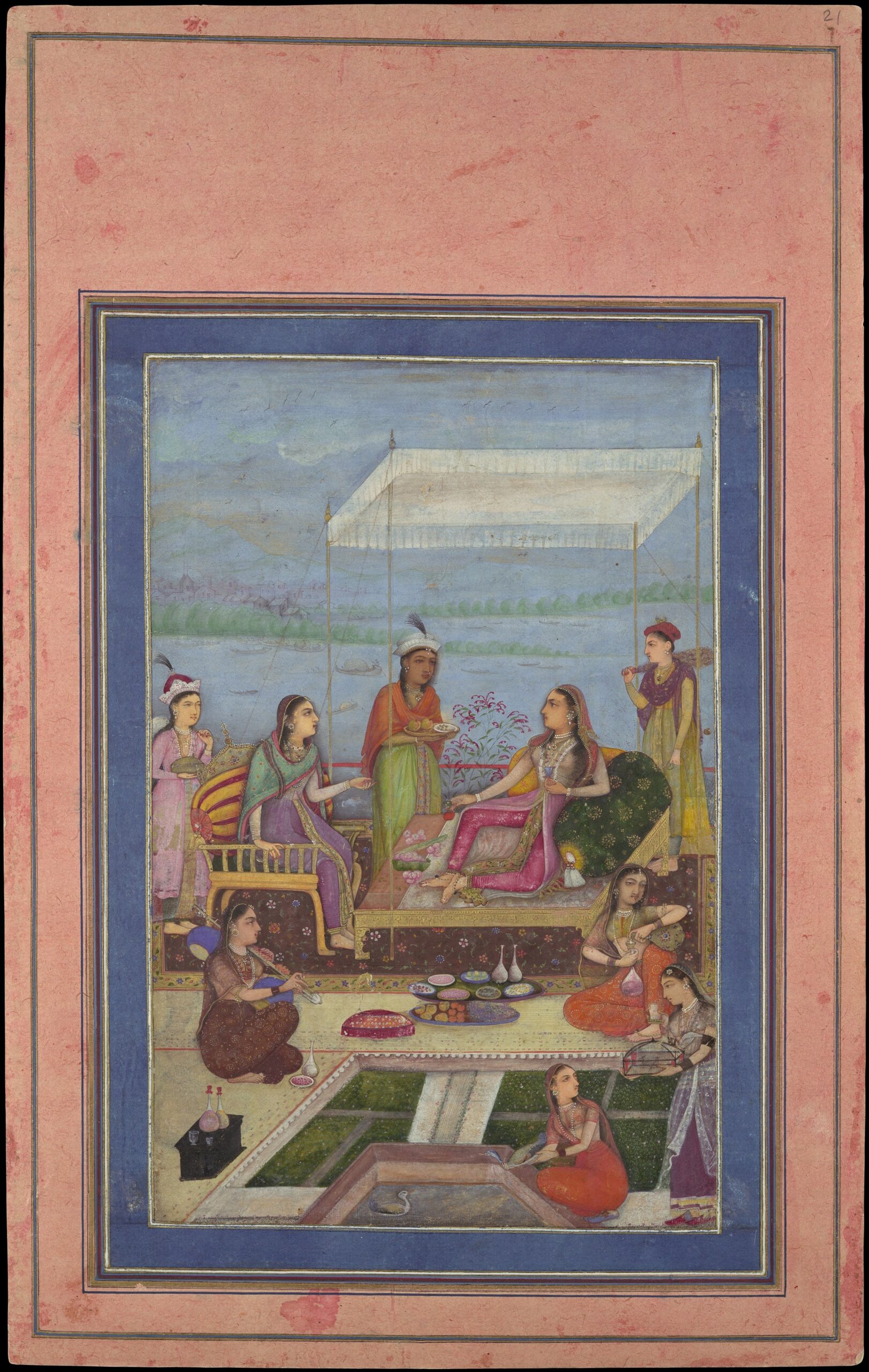

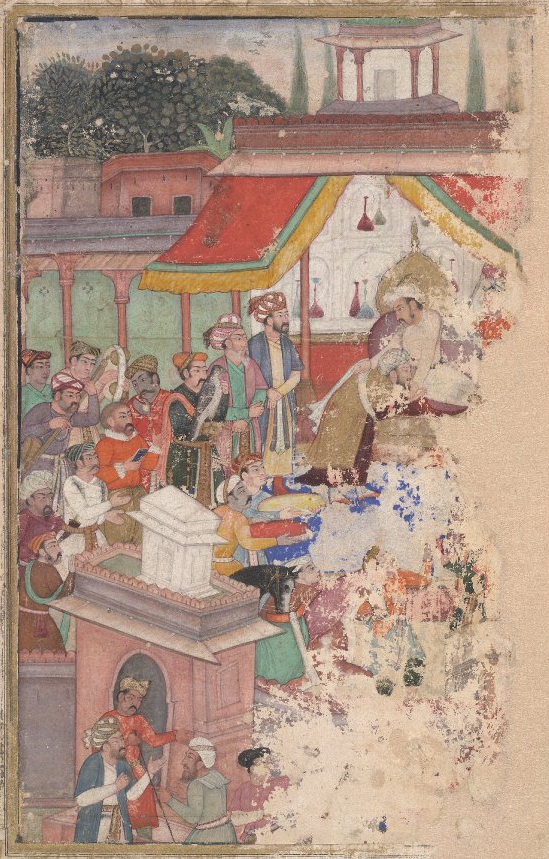

It was both heartening and stimulating to see such a broad range of fields, disciplines, and perspectives brought into fruitful conversation across the week. For Day 1, sessions on ideas of transculturality, identity, and contemporary cultural perceptions provided a useful broader context for the conversations to come. A session on recording early modern travel experiences discussed rhetoric, life-writing, imagined worlds, and the racialisation of sound across several different forms of travel writing, confessional literature, and even legal examinations. The people who wrote these texts and imagined these worlds were the subject of the second session of the day, with papers on creative Italianate English identities, diplomatic belonging at the Mughal court, the perambulations of Italian performers in England, and the extent of female mobility in the period. In the afternoon, three five-minute lightning talks on animal and human go-betweens were followed by a session on cultural perceptions and seventeenth-century academic knowledge of Islam and ideas about Ottoman Culture. The final event of the evening, a roundtable organised by the Medieval and Early Modern Orients (MEMOs) project, took a wider lens to these kinds of cross-cultural encounters, providing fascinating insights into the social, political, economic, and cultural exchanges between England and the Islamic worlds in the early modern period.

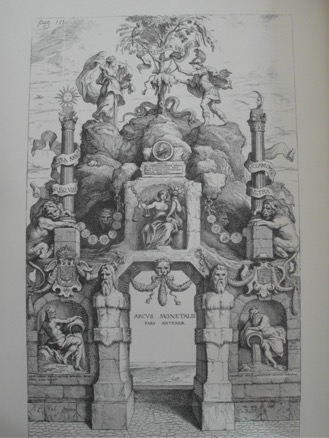

Day 2 opened with a panel on the geographies of devotion, taking us from Caribbean pearl fisheries to the Ottoman Empire, and out on the open ocean for thoughtful discussions on seventeenth-century colonial meditations, Anglican obsession with the Greek Orthodox Church, and the religious significance that one English traveller gave his maritime experiences. In the afternoon, the sessions focused more on language, multilingualism, and different forms of translation. Following two insightful lightning talks on borderscapes in Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko and the Welsh heritage of two celebrated Italianate Englishman, a session on early modern translation cultures tackled standardisation, facilitating English access to Italian republicanism, and the role and representation of native interpreters in a celebrated translation of Peter Martyr. This session, comprised of members of the Paris Early Modern Seminar and the Translation and Polyglossia in Early Modern England project, provided attendees with fascinating and wide-ranging insights into the world of early modern polyglossia, from Italian miniatura to English limning, loanwords, the political ambitions of ‘truthful’ chronicles, and transcultural terminologies. The emphasis that all of these papers placed on the multiplicity of meaning attached to single terms led nicely into the final event of the day: the launch of Keywords of Race, Identity and Belonging in Early Modern England, a collection of essays on terms that were central to the conceptualisation of identity, race, migration, and transculturality in the early modern period. Members of the team were joined by Professor Jyotsna Singh to discuss the origins of the project, the process of choosing, drafting, and editing the keywords, and using the essays in KS3, undergraduate, and postgraduate teaching to interrogate ideas of belonging both then and today.

Day 3 focused more on conceptualisation of difference and belonging in a commercial and colonial context, beginning with an extraordinary roundtable that traced the debates over and development of foreign birth in English law. This was followed by a session on joint-stock companies, with each of the three panellists speaking on either culture, community, or corporation as/for overseas governance. An afternoon session continued on the theme of proto-colonial venture, with participants speaking on various attempts to map and demarcate difference and belonging in works of navigation, political commentary, and chorography. The often violent displacement that occurred when these imperial ambitions were realised was explored in the next panel with presentations on translation and enslavement, nonvolitional travel, and the exile’s continual search for home. Our role in presenting these stories and texts was the subject of the day’s last event, a rich insight from esteemed scholars on the process of editing early modern travel and colonial writing.

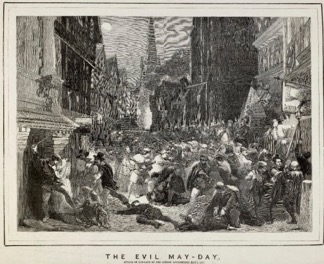

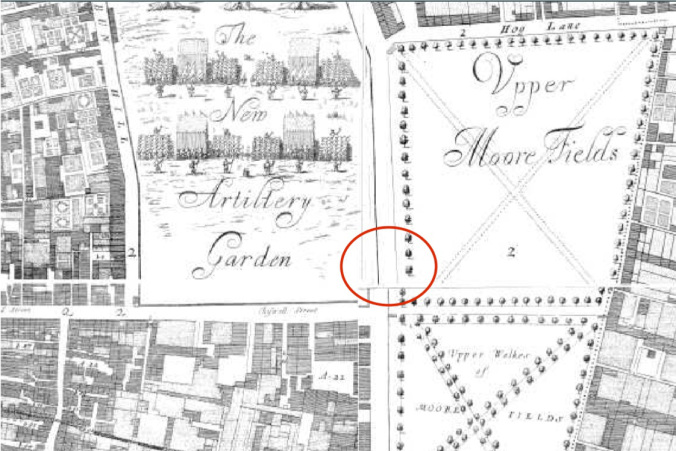

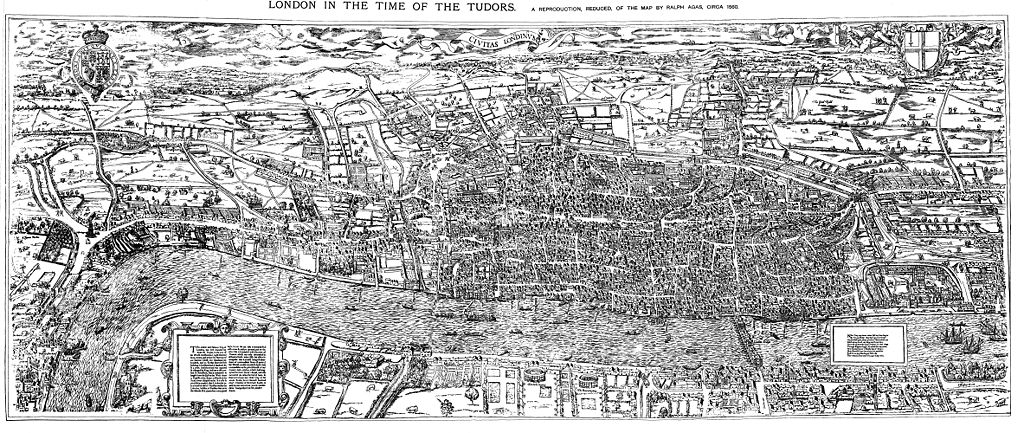

On the fourth and final day of the conference, attendees were treated to a whistle-stop tour of migrant London, with papers looking at multilingualism at the Royal Exchange, the Evil May Day riots of 1517, Italian gardens, and needleworkers of African descent in the parish of St Botolph without Aldgate. We then turned to the representation of these migrants and other groups on stage and in print with fascinating papers on humoral discourses of race and female otherness in Shakespeare’s plays, women under siege in English romance, and the construction of English and Moorish identities in the playhouse. The following session focused on a different, exceedingly popular kind of early modern entertainment: bear-baiting. The AHRC-funded Box Office Bears project treated us all to a masterclass in interdisciplinary research with insights into historical bear-baiting from theatre scholars, geneticists, archaeologists, and Zooarchaeologists. With our appetite for more ursine research whetted, the final event of ‘On Belonging 2’ asked us to consider the implications of the so-called ‘ontological turn’ on early modern conceptions of transculturality. For a conference that brought together scholars working in different fields both in the humanities and STEM, a discussion of Viveiros de Castro’s essay ‘And’ which posits the question, ‘what is at stake in this seemingly innocuous yoking together of heterogeneous fields?’, was a suitably challenging and provocative note to conclude on.

When organising a conference of this size using a more or less unfamiliar format, one is bound to run into some challenges and obstacles, even when in the safe hands of our superb tech team: Dr Sam Robinson, Dr Amy Chambers, and Dr Peter Good. However, perhaps the biggest challenge we faced when putting ‘On Belonging 2’ together was creating a productive, sociable, and safe space for participants and attendees. We like to complain about sour wine and suspicious sandwiches at conference coffee and lunch breaks as much as the next person, but that is also where we get to meet the scholars in our field, enthuse about each other’s work, and formulate new ideas. With most of us spending the year in lockdown unable to visit friends, family, and colleagues, and adjusting to the restrictions on research and teaching, we felt it more important than ever to try to replicate this space virtually. The team organised two social events, one for participants and one for attendees. The evening preceding the first day of On Belonging 2, Dr John Gallagher and TIDE’s very own Dr Tom Roberts organised an early modern travel-themed quiz for speakers and chairs. It was a roaring success thanks to John’s matchless hosting ability and some wonderful prizes courtesy of Amsterdam University Press, the Hakluyt Society, and Cambridge University Press. The second social event for both participants and attendees was hosted on the Wonder.me platform. Wonder is a virtual social space in which people can move an avatar between a number of designated ‘areas’ in a room using their trackpad/mouse/arrow keys. Once you move your avatar into an area, you automatically join a Zoom-like video chat with all the other people in that area. In this sense, it imitates that kind of large-group socialising where you can move easily between different groups to talk more with other attendees. Alongside ‘The Mitre’, ‘The Bear’, and other early modern spaces of conviviality, we also set up several areas as virtual ‘publishers’ tables’ where representatives from the Society of Renaissance Studies, Amsterdam University Press, and the Cambridge Elements in Travel Writing series could speak to any interested party about current/forthcoming publications and events.

The atmosphere of conviviality and support during this event and the conference as a whole was a testament to the kindness and generosity of many of those working in our field. We are proud that ‘On Belonging 2’ successfully fostered new and deepened old relationships between scholars of all career stages. Through our shared interest in examining the voices of people inhabiting transcultural spaces, we hope that TIDE has helped build a transnational and transcultural community to continue querying the established canon.

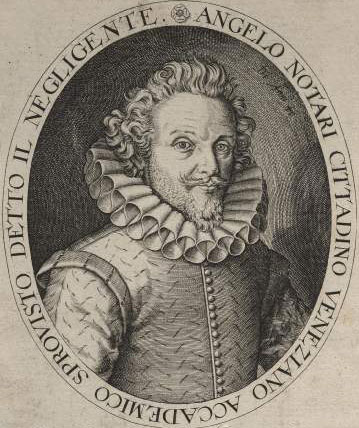

Che portasti tu d’Italia? (What did you bring from Italy?)

Io ne portai a fatica la vita (Barely I brought my life)

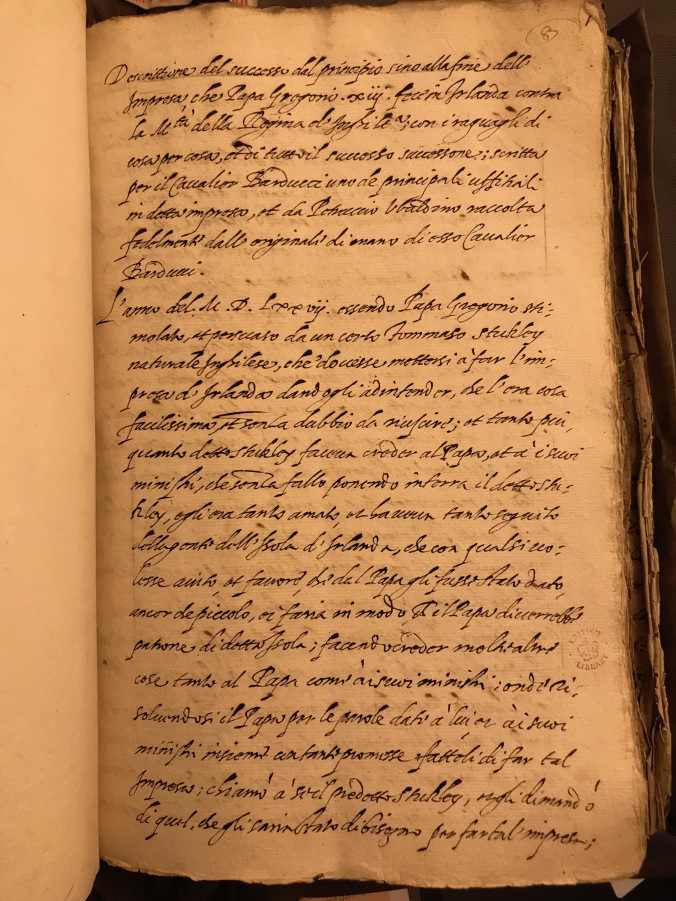

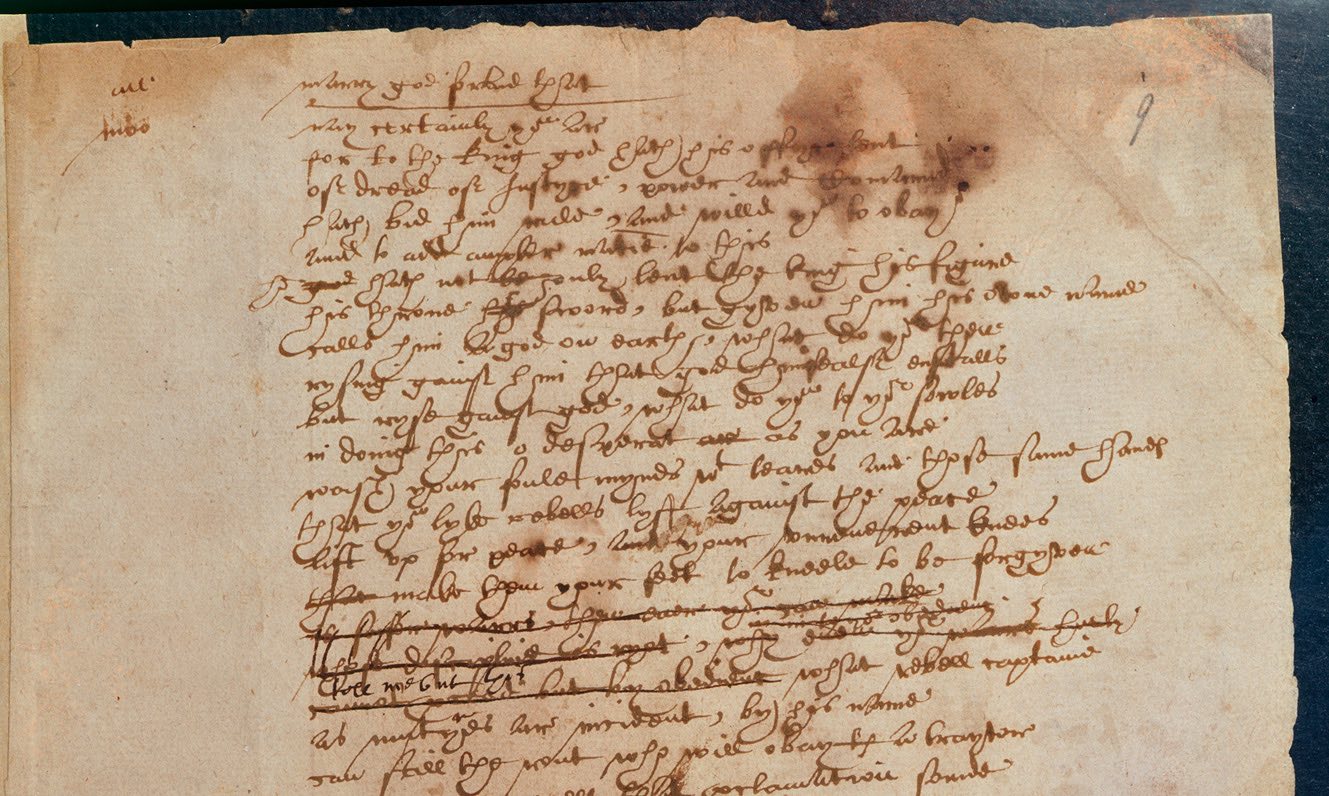

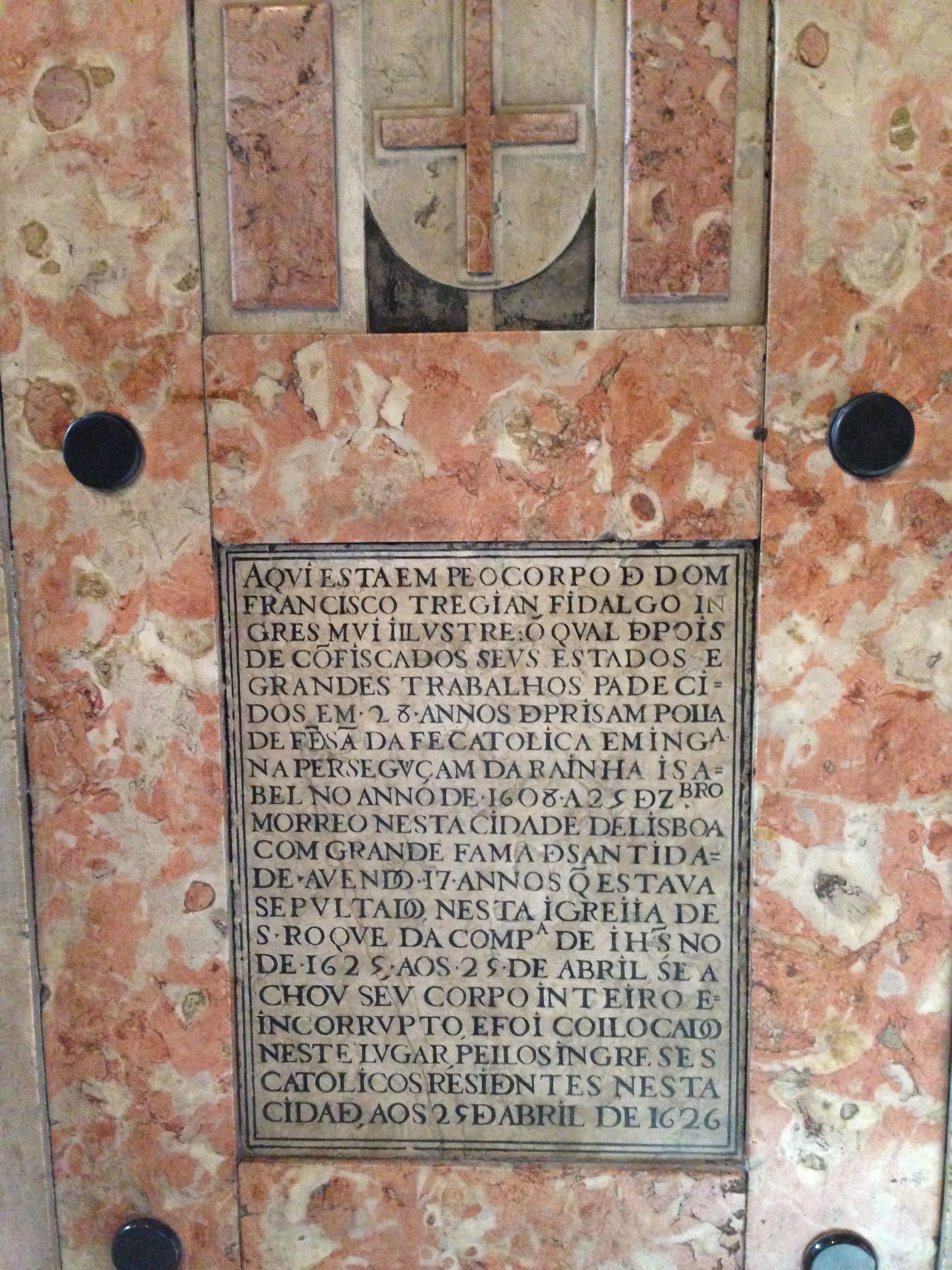

Michelangelo Florio’s (1518-1566) biography as an Italian religious refugee in London transpires in this short dialogue in his manuscript grammar Regole de la Lingua Thoscana (Rules of the Tuscan language) dedicated to his young aristocratic student Henry Herbert (c.1538- 1601) in August 1553.

Around a year before, the Florentine Florio interrupted his public role in the Italian Church in London after economic and doctrinal contrasts with other Italians, and an accusation of sexual abuse. Thanks to the interest of powerful figures (the Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, the King’s Secretary William Cecil, and the Lord Protector of England John Dudley,) Florio became private tutor of Henry Herbert and his sister-in-law Jane Grey. In fact, another undated version of the grammar was dedicated to Jane Grey who became queen for few days (10th - 9th July 1553), just one month before Florio’s dedication to Herbert.

Florio’s grammar was an advanced and less schematic alternative to William Thomas’s Principal Rules of Italian Grammar (1550), the first printed Italian grammar for English speakers. The Florentine praised Guilielmo Thomas’ grammar, but in his opinion, he proposed a better version thanks to more precise and extended explanations, especially in regard of the adverbs. However, the Italian could not publish his grammar in London. As the new Queen, Mary I, ordered the execution of Jane and the banishment of protestants in England, Florio had to flee once again in March 1554, starting a new life in Soglio, in the Swiss Grisons.

In his Regole, Florio included Italian exemplary sentences provided of Latin translations for maggiore chiarezza (better clarity) following each explanation of grammatical rules regarding articles, nouns, verbs, adverb, and other parts of speech). Most of these sentences tell us between the lines that the author was a religious refugee and anti-papist, i.e. a new kind of immigrant compared with the Italian merchants and bankers that had traditionally operated in England since the thirteenth century CE.

Indeed, Florio did not send clothes to Italy and bring wine back as did the merchant protagonist of few examples in part xvii of the grammar. In fact, Florio’s dramatic story appears in the subsequent example where a person brought his life from Italy instead of goods. Here he alluded to the twenty-seven months that he spent imprisoned and tortured in Rome, and the other persecutions encountered, due to his preaching of reformist doctrines in several Italian cities such as Rome, Naples, Padua, and Venice in the 1540s. Finally, Florio fled Italy reaching England on 1st November 1550 and taking on Bernardo Ochino’s position as minister of the Reformed Italian Church in London. Ochino was a celebre reformist preacher who had, since 1547, consolidated a corridor to the country of the protestant king Edward VI for Italians escaping religious persecutions.

Numerous sentences show Florio’s attempts to suggest an assimilation between his situation of unjustly persecuted individual to the one of the Church of England. For example: Quando fui tenuto in pregio dal Papa, non ero amato da Dio. Hora che dal Papa sono perseguitato, son’ certo che da Dio sarò tuttavia difeso (When I was appreciated by the Pope, God did not love me. Now that I am persecuted by the Pope, I am sure that God will defend me in any case). These models created to explain grammatical points (e.g. passive sentences and past participles in the previous sentences) offered Florio chances for fashioning himself to enter the grace of his new powerful anti-Catholic English protectors i.e the Greys, the Herberts, William Cecil Lord Burghley, and John Dudley Duke of Northumberland.

Moreover, Florio believed that language students and Christians both needed to find truth for themselves in their reading; even against authorities as it emerged in the sentence La dottrina del Vangelo piace à ognuno in fuori che al papa (Anyone likes the doctrine of the gospel but the Pope). So, often facing the impossibility of giving a regola ferma (firm rule) the personal preferences and explanations of grammarians, such as Florio himself or Pietro Bembo, could be ignored if more convenient for the language learning process. Ultimately the students had to find their way reading the authors: [...] qui potrei confermar’ quanto v’ho detto con l’autorità di Dante, del Boccaccio, e del Petrarca; ma sarei troppo lungo; leggendogli voi troverete la verità. (Here I could confirm what I said with the authority of Dante, Boccaccio and Petrarch. But I would be too verbose. Reading them you will find the truth).

Florio described himself as a povero forestiero (poor stranger) in the dedication to Herbert, but at the same time signalled in the entire grammar that he was not a ’spiritual stranger’ in England. Also, his grammar shows how his religious beliefs, and the practicality acquired teaching Italian language to foreigners, shaped his vision of the wide theoretical discussion on Italian codification (la questione della lingua). This discussion stimulated, during the same years, the valorisation of English language, in a nationalist and religious key, by Italianate and reformist authors such as William Thomas and Thomas Hoby.

Michele Piscitelli

University of Birmingham

Mxp792@student.bham.ac.uk

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/michele-piscitelli-b7005375/

Midlands4cities Doctoral Training Partnership: https://www.midlands4cities.ac.uk/student_profile/michele-piscitelli/

Biography

Michele Piscitelli is a Ph.D. candidate at University of Birmingham, with a thesis on the presence, teaching and learning of the Italian language in sixteenth century England; in particular the project aims to certain gaps in the literature focusing on the pre-Elizabethan period and alternative sources for language learning beyond Italian-English manuals and vocabularies.

Between 1671 and 1677 John Covel, an Anglican cleric and fellow at Christ’s College, Cambridge, served as chaplain to the English embassy to the court of the Ottoman Empire. During this time, Covel travelled across large parts of Thrace and Asia Minor, before returning to England via much of Greece, Italy and France. Over the course of his travels, Covel devoted a considerable amount of time and energy to studying the Greek Church. This is hardly surprising, given that many Anglicans in this period regarded Greek Christians – because of their geography and history – as witnesses to ancient Christian tradition, who might be relied upon to clarify contentious points of doctrine between – and among – Catholics and Protestants. Covel certainly harnessed his engagement with the Greek Church in this way, using his experiences of Greek worship to intervene in a contemporary dispute among English divines over the use of the sign of the cross, particularly in baptism, where it was commonly performed over the forehead of the baptised.

In the second half of the seventeenth century, English Protestants were divided over whether the sign of the cross was a fundamental Christian behaviour, or simply a superstitious rite which had developed out of the Roman corruption of the faith in the Middle Ages. For the Presbyterian minister Richard Baxter (1615-91), the sign of the cross was ‘a (transient) Image, used as a means of Worship’, and ‘Therefore unlawful by the Second Commandment.’[1] Covel was of a completely different mind, however, owing partly to his encounter with the Greek Church in the Ottoman Empire, which had taught him the value of the practice.[2] In his correspondence, Covel related a story about ‘a poor Greek’ sentenced to death by the Ottoman authorities, whom he watched during his trial and execution, noting that:

when either he could not speak, through weaknesse of body or anguish of mind or else could not be heard amongst the thronging multitude, he in a manner continually made the sign of the crosse upon his breast, to signify to the world by this dumb Rhetorick his undaunted resolution of being and dying a true Christian. I confesse it made me wth great pleasure reflect upon that antient Rite used by our church in Baptisme, I mean ye sign of the Crosse.

Covel’s description here of the sign of the cross as ‘that antient Rite used by our Church in Baptisme’ was significant in and of itself, for it pre-empted the common criticism that it was merely a Medieval Catholic invention, without precedent in the early Church. In any case, Covel conceded that the sign of the cross ‘may seem a very uselesse and empty ceremony’, whether in baptism or among adult Christians, ‘to men that never lived abroad amongst unbelievers, nor considered the state of the primitive Church by which this practice prevayled’. Yet of course Covel, unlike most of his compatriots and colleagues, had ‘lived abroad amongst unbelievers’, where he had witnessed the persecution of Christians at the hands of the non-Christian Ottomans, which provided him with a different perspective on the sign of the cross. For under these circumstances, Covel had found the practice very useful, for it signified ‘throughout the whole world, where no other language is understood, that the person so signed is own’d, or owns himself to be a member of Christ’s body.’ By way of illustration, Covel informed the recipient of his letter that in Ottoman territories, the sign was commonly used by local Christians to ‘begge your charity, when all language is insignificant’. Covel also recalled using the sign himself, when he had travelled ‘in Turkish habit [or dress]’, in order to reassure frightened local Christians that he was of their faith, and thereby ensure that he was ‘immediately admitted and kindly treated’ by them.

Covel had therefore seen what it must have been like for those early generations of ‘primitive’ Christians, surrounded by ‘unbelievers’ and subjected to frequent bouts of persecution. Although English Christians no longer faced such challenges, the sign of the cross, even if used only in baptism, remained a potent symbol of Christian solidarity, of one’s resolution to ‘maintein the inward and spirituall fight against sin and the Devil’, and a crucial reminder that Christians, wherever they found themselves, ‘should not be ashamed publickly, even by this outward sign, to confesse to ye world and all the powers’ their faith in Jesus Christ. In Covel’s view, the sign of the cross was part of the ‘universal Character of a Christian, which was wisely introduced by our forefathers and ought still to be used’, particularly in baptism.

Thus Covel believed that his direct experience of a Church persecuted by non-Christians gave him unique insight, noting, as we have seen, that the sign of the cross only appeared useless to those ‘that never lived abroad amongst unbelievers’. In using the Greek Church to defend the practice, Covel distinguished himself from several of his Anglican colleagues, who championed the sign of the cross using the writings of theologians from the early Church. In so doing, Covel suggested that overseas travel, and exposure to religious diversity specifically, equipped one with a better sense of right belief and devotion, particularly when it came to contested issues such as the sign of the cross. Indeed, Covel’s defence of the sign of the cross vis-à-vis the Greek Church testifies to the role of early modern travel, and of transcultural exposure, in shaping and shifting travellers’ views of familiar debates at home, in ways that often distinguished them from their non-travelling contemporaries.

Fig. 1: Portrait of John Covel, c. 1716. Painted by Claude Laudius Guynier (fl. 1713-16), oil on canvas. Available via Wikimedia Commons.

Fig. 1: Portrait of John Covel, c. 1716. Painted by Claude Laudius Guynier (fl. 1713-16), oil on canvas. Available via Wikimedia Commons.

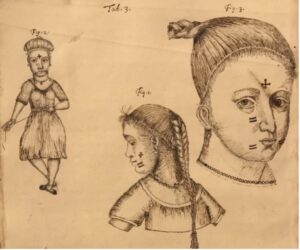

Fig. 2: Covel’s sketches of Bedouin women in North Africa, whose faces were inked with crosses, though they had long since converted from Christianity to Islam. See British Library (hence BL), Add. MS 22912, 27v.

Fig. 2: Covel’s sketches of Bedouin women in North Africa, whose faces were inked with crosses, though they had long since converted from Christianity to Islam. See British Library (hence BL), Add. MS 22912, 27v.

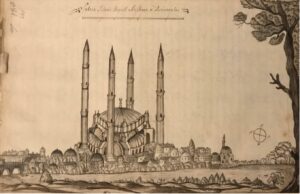

Fig. 3: ‘Sultan Selym’s Royall Mosque in Adrianople’, drawn by the French artist Jerome Saltier, whom Covel met in Izmir. See BL, Add. MS 22912, 231r.[3]

Fig. 3: ‘Sultan Selym’s Royall Mosque in Adrianople’, drawn by the French artist Jerome Saltier, whom Covel met in Izmir. See BL, Add. MS 22912, 231r.[3]

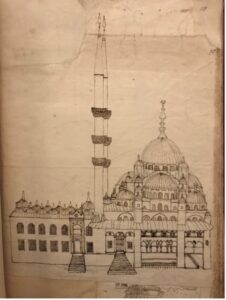

Fig. 4: Covel’s sketch of the New Valide Mosque in Istanbul. See BL, Add. MS 22912, 118r.

Fig. 4: Covel’s sketch of the New Valide Mosque in Istanbul. See BL, Add. MS 22912, 118r.

[2] Covel’s remarks about the sign of the cross are quoted from John Covel, ‘A peice of my letter to Dr Womock about ye Crosse in baptisme’, date unknown, London, BL, Add. MS 22910, 115.

[3] See also Jean-Pierre Grélois, ed., Dr John Covel, Voyages En Turquie 1675-1677. Texte Anglais Établie, Annoté et Traduit Par Jean-Pierre Grélois (Paris: P. Lethielleux, 1998), 108–9.

Charles Beirouti

University of Oxford

charles.beirouti@new.ox.ac.uk

Biography

Funded jointly by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and New College, my research centres broadly on the depiction of religious diversity in seventeenth-century English and French travel accounts, particularly those written by clerics who lived, worked and travelled in the Islamic world, stretching from the eastern Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. My broader research interests include seventeenth-century European travel and travel literature; Europe’s relations with and perceptions of the Islamic world from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment; seventeenth- and eighteenth-century British and French history, particularly religious and intellectual; the practice of Islam in the seventeenth-century Islamic world, particularly in the Mughal and Ottoman empires; and non-Muslim communities in seventeenth-century Islamic states, particularly Eastern Christians.

Something I’ve repeatedly come up against in my doctoral research is the perception of early modern England as a homogenous entity. Matthew Greenfield has rightly observed the problematic depiction of ‘English culture as a homogenous entity with clear boundaries, uncomplicated by the British question’. Happily, recent scholarship has done much to counteract this depiction, redirecting our attention to England’s elision and oppression of its archipelagic neighbours and to the uncertainties this produced. I want to try and apply this thinking more locally. Perhaps in addition to being complicated by ‘the British Question’ the ‘nation’ is complicated by what we might call ‘the English Question’. To that end, I’d like to turn to an underexplored moment in Henry V: the dispute between Corporal Nym and Ancient Pistol, to suggest that the oppositional dynamics of Henry V are not limited to England’s archipelagic or continental neighbours but encompass a wide variety of tensions within England as well.

We first encounter Nym bemoaning his lot in II.i, having lost both his fiancée and eight shillings to his erstwhile friend Pistol. Taken on its own, the scene is a humorous episode between two of Falstaff’s former drinking companions, preoccupied as usual with women and money. But when set against the backdrop of the civil unrest in Henry IV and the foreign conflict of Henry V, the scene raises questions. Just how unified is Henry’s ‘band of brothers’? The play as a whole insists on ideals of friendship and brotherhood while at the same time challenging and interrogating our assumptions regarding the unity they imply. The first instance of the former word appears in II.i – encountering Nym, Bardolph asks ‘are Ancient Pistol and you friends/yet?’ – and reappears throughout the scene. The interrogative ‘yet?’ sets the tone for the rest of the play, in which the bonds of friendship and brotherhood are repeatedly cast into doubt.

The scene’s position is also significant. This scene displaces treason from its announced appearance; it also offers our first glimpse into popular military discontent in the play. The Chorus’s assurance that ‘honour’s thought/reigns solely in the breast of every man’ – already cast into doubt by its mention of the traitors Cambridge, Scroop, and Grey – is further eroded by the quarrel in Eastcheap, which revolves around two distinctly dishonourable actions: Pistol’s theft of Nym’s fiancée and his failure to pay his debts. Although the scene implies that both issues have been settled, it is by no means clear that this is the case. Pistol and Nym may be ordinary soldiers, but they are also representatives of a national military entity. Their unresolved dissent in this scene points towards broader underlying fractures in the unity of the ‘happy few’ Henry casts in opposition to the French.

Nym and his companions are representative of a broader lack of enthusiasm for the war which runs throughout the scenes with common soldiers, even shadowing Henry’s interactions with fellow noblemen. By studying these moments of intranational conflict, then, we gain a better understanding of popular military sentiment, both in the play and in the cultural context in which it was first performed. At the time of Henry V’s composition there was significant popular resentment regarding both conscription and the fees levied to fund the war in Ireland. This resentment is played out not only in the more disreputable characters of Bardolph, Pistol, and Nym, but in the sentiments of those soldiers depicted as conventionally honourable, such as John Bates and Michael Williams.

Redirecting our gaze to such moments of intranational tension in the play allows us to challenge the idea that England as a whole was a homogenous entity. This might enable us to consider how England’s varied and often conflicted identities were understood by its inhabitants, then as now. In early modern London, for example, playgoers were in the midst of a substantial immigrant community composed of both strangers (those coming from overseas) and ‘Englishmen forren’ such as Shakespeare, who had migrated to London from more rural areas. That is not to say that some degree of division is incompatible with nationhood. Instead, let’s attend to internal divisions alongside those between England and its archipelagic or continental neighbours. Doing so enables us to reconsider Shakespeare’s England as a composite of parts rather than a cohesive whole, offering an alternate perspective on the problematic boundaries of the early modern nation.

Biography:

Chloe Fairbanks is a third-year doctoral student at the University of Oxford. Her research reconsiders Shakespeare’s treatment of national identity through an ecocritical and spatial lens. She is the co-host and co-writer of 'On the Nature of Things', a forthcoming podcast on how people of the past understood and interacted with the natural world. She can be reached on Twtitter @fairban_c.

In the late 16th century William Harborne, English ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, managed to secure a set of capitulations from the Turkish Sultan which reduced tariffs on English goods and paved the way for a fruitful economic relationship that would last until the dawn of the 20th century. Harborne’s friendly relations with the Ottoman elite, coupled with his knowledge of the Levant and diplomatic skill, has earnt him praise from scholars of Anglo-Ottoman history. Naturally, Harborne’s successors have received less attention. It is my intention to redress this imbalance by focusing on two letters written by Sir Henry Lello, who served as ambassador to the Sublime Porte in 1597. Lello’s mission and letters from Turkey highlight Protestant England’s desire to learn more about the Islamic world, but also shed light on the importance of information exchange in Early Modern diplomacy and how knowledge of ‘Eastern’ countries could be politically useful and economically beneficial when formulating wider state policy. Viewed from this perspective, Lello’s successes may have been more subtle than Harborne’s, but is equally deserving of praise.

Sir Henry Lello wrote two letters in relatively quick succession to the English Secretary of State, Sir Robert Cecil. In them, he informs Cecil of the imminent arrival of the Persian ambassador to Constantinople who is ‘expected daily’ and will discuss ‘the redelivery of the towns and fortresses he hath lately taken from the Grand Signour.’ In his next dispatch, written a mere 14 days later, Lello notifies Cecil of the arrival of the ambassador, ‘who was received with great pomp’ and who ‘cometh to demand those two great countries of Tauris and Sheryan, otherwise called Medea, which were won from the Persian by the Grand Signour.’ Lello’s description of the embassy and the relations between the Ottoman Empire and Persia make up a significant portion of his letter, and he goes into further detail about potential unrest in the Ottoman Empire which the Persians were looking to exploit. It must also be noted that Cecil was receiving similar information about Turkey and Persia from other clients, including the Shirley brothers. Furthermore, Lello sheds light on the relationship between the Sultan and Tsar of Russia, stating ‘another (ambassador) from the Emperor of Muscovia for the concluding of a perpetual peace’ is soon expected in Constantinople. Naturally, this leads us to consider why information about Ottoman-Persian relations and their wider diplomatic alliances were important to Cecil and Protestant England.

The most obvious answer is commerce, given the fact that English trade to both Persia and the Ottoman Empire could be sufficiently hampered by prolonged periods of conflict between the two. The Levant Company, set up under a charter by Elizabeth I, helped English trade to the Near East flourish. The English monarch was also keen to start a regular trade with Persia, with her merchants in Russia asking several times for a transit route to be restored along the River Volga, thereby allowing British merchants access to Persian markets. In addition, Lello’s letters could also be politically useful for English diplomacy with other Northern and Eastern powers. Knowing the Tsar was attempting to secure a peace with the Ottoman Sultan had the potential to remove a significant barrier to Anglo-Russian relations, as successive Russian kings, including Ivan the Terrible and Boris Gudunov, constantly questioned English support for the ‘infidel Turk.’

Whilst we have considered the importance of information to Cecil and the monarchy, it is also worth briefly exploring how providing these ‘intangible gifts’ of information on the Islamic world also benefitted ambassadors like Sir Henry Lello. Having written these letters to Robert Cecil in 1599, two years later we find a request from the same Henry Lello to Cecil, asking ‘for favour for his brother Hugh Lello’ ‘who desires some change in martial affairs.’ It seems that in return for providing information about the Islamic world, Lello was able to lobby Cecil for favours, including for members of his family, thus highlighting the reciprocal nature of information exchange in Early Modern England.

Viewing Lello’s mission from the perspective of information exchange allows us to shed a new light on his embassy to Constantinople, not merely as a footnote to William Harbourne, but as a successful diplomat in his own right who acted as an important source of information about the Wider Islamic World. Perhaps more importantly, his correspondence in 1599 also illustrates how important the ‘East’ and wider Islamic World was to the English crown. Given the West’s recent military involvement in the Middle East, there seems like no better time to highlight Lello’s embassy and this period of relatively peaceful exchange.

Shahid Hussain

University College London

Biography:

Shahid Hussain is a current MPhil research student hoping to complete his PhD at University College London (UCL) on the patronage and networks of British Ambassadors to Muscovy in the 17th century. He completed his Undergraduate and Master’s degree at UCL, where he investigated various aspects of Russian History in the Early Modern Period, including the military relationship between Muscovy and the Ottoman Empire during the reigns of Ivan the Terrible and Suleiman the Magnificent. A strong interest in diplomacy and the interplay between The West, Russia and The Islamic World has also culminated in a number of articles on contemporary diplomatic affairs for journals including The Diplomat and Modern Diplomacy. He can be reached on LinkedIn here, or by email at shahid.hussain.10@ucl.ac.uk.

TIDE Salon is a radical new archive: a ground-breaking, interactive multimedia collaboration between TIDE, the award-winning novelist Preti Taneja, six extraordinary sound and spoken word artists (Steve Chandra Savale, Sarathy Korwar, Shama Rahman, Ms. Mohammed, Sanah Ahsan, and Zia Ahmed), curator and creative producer Sweety Kapoor, and critically-acclaimed filmmaker Ben Crowe (ERA Films). It is supported by the TIDE project, and the Humanities Cultural Programme, one of the founding stones of the Stephen A. Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities.

Background to the Project

Alien, stranger, foreigner, traveller, exile, citizen – these words are ubiquitous in contemporary debates about belonging and identity, yet many were shaped by travel, trade, and colonialism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The musicians and spoken word artists produced their work using TIDE’s research and drawing on their own personal histories and stories to ask:

- What do those words mean to us now?

- How does knowing their meaning and migration change our social world?

- Can we communicate across form, distance and time to explore the politics of translation and its lived realities?

From Drawing Rooms to Digital Realms

Though often associated with early modern European literary culture, salons were also prevalent among Asian elites in the sixteenth century. This collaboration takes the intimate ghar (home)-style salon as its inspiration to explore transculturality in the early modern period and today, evoking the creative atmosphere of early modern salons and their mix of scholars, poets, and artists.

‘The journey of words and their meanings that people carry as they travel physically and figuratively from their real and imagined homelands to the lands of their destinies and legacies, formed the conceptual basis in my curation for the TIDE Salon project. Drawing from the inspiring wellspring of the TIDE project research, I sought to bring together artists who embody this complex matrix of space, time, mobility, language, identity, tradition and faith. Along the entwined twins of a jugalbandi—a conversation of two equals whose unique strategies result in new, unpredictable moments of creative kinship—there are also the ghosts of the past, the present and the future who whisper secret incantations into the atmosphere. These special collaborations between six highly talented British musicians and spoken word artists of South Asian descent are in response to operative TIDE keywords, that have journeyed to a moment in time inheriting meaning and heft, and are now subject to contemporary socio-cultural and political forces. The result is a sort of creative register formed of these atmospheric sounds and voices, echoing in turn, the artists’ own histories, memories, conversations, and journeys, not to mention ours as well. The inheritance of words morphs with time, and with the tide.’

– Sweety Kapoor (Curator and Creative Producer)

While the collaboration originally entailed a one-off, ticketed event for a public audience, the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdowns that ensued transformed the project in unexpected ways. The interactive installation that has emerged, created by Ben Crowe (director of ERA Films), showcases the pieces produced by the artists and spoken word poets while simultaneously offering an inside look at the process of collaboration and ‘doing’ history. The installation is a salon, port, and archive all at once: a place where different layers of source material mix and mingle, allowing visitors to hear new music, embark on a series of visual and textual discoveries, and gain behind-the-scenes access into the ideas and exchanges that produce creative work.

‘These creative collaborations between some of our best music and written/spoken word artists, framed by Preti Taneja’s original fiction and drawing on the work of TIDE, reimagine the potential of what a digital archive can offer a Renaissance one, all from a “future archivists” perspective. The installation dissolves the boundaries of time to present the artists’ reconfigurations of the relationship between the distant past and the highly-charged political present: it also mirrors a sense of journey and discovery at the heart of creative work, as well as research, and allows people to form their own narratives from the fragments. It embeds the non-linearity, plurality and interaction necessary to challenge binary narratives of identity, and celebrate the complex mutuality of our social world. I think it's a radical new kind of archive.’

– Ben Crowe (Filmmaker and Installation Designer)

The digital installation allows visitors to navigate their own routes. No two journeys need be the same. From the embarkation page, click the journey map and choose your own voyage through keywords, soundbites, video clips, images, poetry, and literary fragments. These interconnections are meant to replicate the messy, eclectic process of historical research itself, where different ways into source material can influence the stories we tell, and where archives often invite self-reflection and creative expression. You are accompanied by three fragments by Preti Taneja, written as if found by you, as you encounter an archivist and a translator working a century on from now.

‘The fragments are in a unique form: part translation, part diary of desire; one is a ghazal (for “Savage”): they are inspired by and include material drawn from the process of the actual TIDE researchers, the keywords they collaborated on and material and music provided by the TIDE Salon artists, which can be found through the whole installation. I also draw on the work of Sappho, William Shakespeare, Michel de Montaigne, Walter Benjamin, Agha Shahid Ali and more. Working in oral puns, overheard lyrics, canonical texts, original ideas, and found phrases, the fragments can be read in any order – yet they speak to each other, forming a conversation across the installation and offering a story of TIDE, the Salon artists and our times full of isolation, digital connection and pixelated dreams. They allow the researcher to discover them in their own time and space of longing for unity beyond hierarchy, reversing through the installation itself the divisive project begun by Empire, allowing the researcher through interacting with the fragments and the installation to embrace and celebrate hybridity in all forms.’

– Preti Taneja (TIDE Visiting Writer, 2019-2020)

The musical experience we had originally planned for our in-person event has come full circle. While lockdown might prevent us from all meeting in person, you can now experience the salon in your own home. By the seventeenth century, English travellers noted the Ottoman and Persian taste for sharbat (‘sherbert’), a drink made from water, sugar, and dried fruits, flowers, and spices such as peaches, saffron, or mint (when George Sandys visited Constantinople, he wrote of ‘sundry sherberts...some made of sugar and lemons, some of violets, and the like’). So stir yourself a sharbat and journey through the fragments, accompanied by the sound of travellers moving across thresholds, searching for home: ‘open at a page that moves you’.

On November 9 and 11, ERC-TIDE hosted a series of two online seminars coorganised with the LARCA research centre (UMR8225, Université de Paris) on “Polyglot Encounters in Early Modern English Narratives of Distant Travels”. With more than 300 participants from around the world for each session, the topic and attendance were very much in resonance! The speakers took us from the nearly-next-door of Richard Hakluyt’s Christ Church and Thomas Crosfield’s Queen’s College in Oxford to the New World of explorers Jacques Cartier, John Davis, and Thomas Frobisher, with mediator figures ranging from translator John Florio to the supposed Indian descendants of the legendary Welsh prince Madoc. Meanwhile attendance at the seminar ranged as wide as Islamabad, Bogota, Montreal, Dijon and Rome for fruitful exchanges on transculturality and multilingualism in the period.

The two sessions aimed at exploring the practices and strategies underpinning polyglot encounters in travel accounts produced or read in England. Drawing on linguistic, lexicographic, literary and historical methodologies, we looked into some of the contexts and significances of textual contact zones and communication circuits. Particular attention was paid to uses of polyglossia in processes of identity construction, defining and promoting national and imperial agendas from commercial to university circles, appropriating and assimilating foreign linguistic capital, but also meeting resistance and limits from linguistic and cultural others refusing to lend themselves to subaltern status.

For the first session, Andrew Hadfield (University of Sussex) beautifully guided us through some of the ways in which the Madoc legend, propped up by fanciful etymologies of Indian words, was enlisted to serve the Anglo-British agenda of imperial expansion. Sarah Knight (University of Leicester) aptly followed on the commercial and scholarly ramifications of imperial thinking, unpacking early modern English universities’ rhetoric in addressing cultural and linguistic difference through sartorial analogy.

For the second session, Donatella Montini (University of Sapienza Rome) cogently complicated existing models of translation/communication circuits by considering the case of deliberate retranslations, focusing on the textual journeys of Cartier’s account of his Canadian voyages through Florio’s choice of translating them out of the Italian of Ramusio’s Delle Navigationi e Viaggi rather than their original French for Hakluyt’s Principal Navigations. Mat Dimmock (University of Sussex) brilliantly nuanced questions of identity and authority by looking at the records of Inuit vocabulary in accounts of Frobisher’s and Davis’s journeys in the Far North, with natives turning the tables around on their “discoverers” by pointing at their difference and their singularity.

These two engagingly rich sessions were chaired respectively by Laetitia Sansonetti (Université Paris Nanterre, Insitut Universitaire de France) and Sophie Lemercier-Goddard (Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon, IHRIM). The material covered throughout will be part of the larger project of “Translation and Polyglossia in Early Modern England” and its “Polyglot Encounters” series with Brepols Publishers, under the general editorship of Ladan Niayesh and Laetitia Sansonetti.

For the practical organization of these events, we are much beholden to Rachel Willie and the Society for the Renaissance Studies, opening to us the beautiful showcase of the SRS Crowdcast platform, where recordings of both sessions will be kept:

Ladan Niayesh

By the time I completed planning the semester-long arc of an undergraduate seminar on ‘Movements, Migrations, Memories’ for The Ohio State University’s English course on ‘Studying the Margins: Language, Power, and Culture,' I was sure I wanted to use TIDE Keywords in my class as testaments to the changing valences of words we think we know, but which have multifarious and sometimes surprising histories of usage. I wanted my students to take away that language is not neutral, that it has a history, and that that history is not unconnected from prevailing ideology.

My course was designed for students to ‘consider contemporary texts in a variety of genres as we examine how movements, often at the intercontinental and planetary level, form and inform our current sense of human inhabitation of the earth and our responsibilities towards each other in an era of unprecedented mass migrations and human influence on the natural world’ (from the course description in my syllabus). The course goals were: a thoughtful sampling of a variety of contemporary works exploring movements, migrations, and margins; developing awareness of and empathy for familiar and unfamiliar ways of longing and belonging in the world; inculcating methods and strategies for interpreting complex ideas and language, and explaining those interpretations in precise oral and written work.

Most of our readings were in recent or contemporary writings: Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do (New York: Abrams, 2017); Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019); Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West (New York: Riverhead Books, 2017); Valeria Luiselli’s Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2017); Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (London: Vintage, 2008); and many of the Refugee Tales from the three volumes edited by David Herd and Anna Pincus (Manchester: Comma Press, 2016, 2017, 2019). In addition to these readings which would eventually lead to the term papers (on research questions of the students’ choosing), however, there were also short readings geared towards oral presentations. That is where TIDE Keywords came in. Students were asked to read the TIDE Keywords Introduction for an orientation of why the keywords warranted a close look, and to pick one keyword to read thoroughly about and present on. The goal was to collectively hear about as many keywords as possible in the class—a class of seventeen—and we therefore didn’t want to “repeat” keywords. The questions that each presentation had to address were:

- - what is the history of the keyword in question? (i.e., please provide a summary of what you read in your Keyword chapter.)

- - what in the history of the keyword you read has been surprising to you, as you encountered that history from a 21st-century perspective?

- - having read the keyword of your choice, what contemporary examples/issues/matters come to mind, and why? (i.e., how would you connect what you read to the world around you today?)

- - and finally, open-ended-ly: what questions came up for you?

Each student would present their keyword for fifteen minutes, with up to fifteen more minutes for subsequent comments and questions. After the day’s presentation, the student would also summarise the main points of their presentation into a single-page document and submit it to me through the class website on Canvas. In my evaluation, I would grade along the following criteria: the student’s ability to address the assignment prompt; the student’s clarity of comprehension and presentation (i.e., their care about the comprehension of the rest of the class); their engagement with what they read and their ability to make cogent and thought-provoking connections with the world they lived in; and their ability both to ask substantive questions of their classmates and to field questions that they received. Students were welcome to bring PowerPoint slides for their presentations, if they wanted to.

As my students picked their keywords, the choices varied between what they thought they knew, and what they knew they didn’t. For instance, if ‘Foreigner’ was an apparently known concept, ‘Denizen’ was not; if ‘Jew’ was potentially known, ‘Blackamoor’ was not; if ‘Merchant’ was possibly known, ‘Mercenary’ was not. Since the editors of the TIDE Keywords have provided such a rich array of known-unknowns and almost-knowns, and since the appearance of the keywords on the web page encourages scrolling and browsing, my students had no trouble picking seventeen different keywords on the day of the sign-up. The choices came accompanied with comments such as ‘I know what this word means now, or I think I know—but I wonder what that word meant in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,’ or ‘I mean, it’s still English, but is it the same English?’ or ‘I’ve never heard that word before, I want to know what it means!’

The presentations occurred over a period of five weeks, with up to two presentations in each class meeting, and the class meetings themselves held twice a week. Owing to the US lockdown over COVID-19 in spring 2020, a couple of presentations carried over to online formats. Whether the presentations happened in person or online, the students consistently demonstrated both genuine curiosity and engaged attention with one another. I see this as a testament both to the intellectual integrity and generosity of my students, and to the accessibility of the keyword chapters themselves. The students wanted to do the reading and did do the reading. And, in a few cases, students also ‘read along’ with their classmates even though they were not themselves responsible for presenting particular keywords. This, of course, only led to richer discussions, with the work of a few helping to propel the whole class into deeper conversations and more thoughtful back-and-forth. In keeping with my pedagogical principle of facilitating situations where students can and even must teach each other, I usually held back for the first ten minutes of the q-and-a unless specifically asked (when I was specifically asked, it was usually where a student wanted to double-check with me about historical context). I knew, and my students knew, that the weight of the class discussions was on them—and they carried that weight beautifully.

Here are some of my favourite instances from the questions and comments I heard, and also had the pleasure of responding to or building on over the weeks of the TIDE Keyword discussions: ‘You know, being a denizen sounds like being a second-class citizen—like if you’re from Puerto Rico [and in the US]. We like your taxes, but we don’t like you.’

- ‘You’re saying that being a pirate was actually legal?!’

- ‘I knew that people couldn’t have been calling themselves pagans—it was the Christians calling them that. Which explains some of the things they [the Christians] said about them [the pagans].’

- ‘I’m seeing that Merchant of Venice speech about an ‘alien’ plotting against a ‘citizen’ now in a whole new light.’

- ‘The word they’re using is ‘rogue,’ or even ‘gypsy,’ but really, they’re using these categories to define disability, in a way. Otherwise why go on about the ‘sturdie’ beggar or vagabond?’

- ‘The way we refer to people, that is, the terms we use, has consequences for how people are legally treated.’

- ‘Wow, I didn’t know that passports were something that not everyone could get!’

- ‘Can one become a stranger in their own home/country?’

- ‘So, the nervousness about the alien is a nervousness about their allegiance, isn’t it? And I also thought about how we hear a lot of ‘yes, please bring your diversity to this country [the US]’ but at the same time, ‘now please learn English and perform your belonging’.’

- ‘That reminds me, did you know that a study found that a whole lot of US citizens could not pass the US citizenship test?’

One fallout of this emphasis on discussion was that we often spent half the class period on the presentations and the lively deliberations and debates that took off. In a class time of 80 minutes, we frequently spent 45 minutes on two TIDE Keyword presentations. I don’t regret this, because as the days passed, I inculcated some important skills myself: of explicitly building aspects of the students’ discussion into my own lectures (for instance, of an ‘alien’ condition as having parallels in the lives of unaccompanied minors crossing the US-Mexico border, as Valeria Luiselli’s book discusses); of offering some summative comments and remarks to further contextualise the keywords for the class (for instance: yes, ‘Indian’ remains a very fraught word, especially in the US, with this country’s history of Native genocide); and of generating keywords-related study-questions for texts we were about to read (for instance: in Amitav Ghosh’s novel, what picture do we get about the belonging and loyalties of a global ‘citizen’?). It is also—always—a joy for me when the point-following-point kind of discussion that I have modelled for my class is actually taken up and emulated by my students—and I can sit back for a while and just steer. But when I do this TIDE Keywords assignment again, I shall provide a bit more scaffolding—telling students, for instance, how much time to spend on each part of the presentation (I shall recommend no more than 3 minutes), and asking each student, before their presentation, to send on to the rest of the class a paragraph of about 300 words outlining the thrust of their initial interest and findings (something along the lines of ‘I started this research because I thought I knew or wanted to know X, I found out Y, and I shall talk in class about the connections with Z’).

In a mid-term check-in, and in end-of-term reflections, students documented how valuable they had found their engagement with the keywords. One student wrote: ‘Much of my learning in this class came from our in-class discussions that followed our keyword presentations. The presentations were great because they allowed me to learn the origins of key English words and how those words were used to push ideologies and oppress marginalized groups. And with this, our class discussions that followed allowed us to address tough questions regarding these topics of oppression, and receiving varying viewpoints on these questions helped open my mind to various possibilities.’ Another wrote: ‘[Without the TIDE Keywords assignment] I would have never seen parts of history repeating itself again and again, I learned so much from my own keyword project that I would have never expected to learn.’

I shall close with a mention of one final and valuable aspect of the TIDE Keywords: that they are free and open-access. I teach on a campus where students often struggle to purchase or rent textbooks. To me, to them, the TIDE Keywords functions as a gift.

Amrita Dhar

dhar.24@osu.edu

In 2019, ERC TIDE and the Runnymede Trust created a twelve-week professional development programme to provide teachers with subject expertise, practical experience, and pedagogical methods to reinvigorate their curriculums. The Beacon Teacher Fellowship enabled and empowered teachers to develop creative and innovative approaches to the teaching of empire and migration. Findings from the Fellowship and the research of TIDE and the Runnymede Trust resulted in the Teaching Migration, Belonging, and Empire report that was presented to government in parliament in July 2019 by Jason Todd, Kimberly McIntosh and Nandini Das, supported by the Beacon Fellows and TIDE researchers.

A year on from the fellowship, I’ve asked some of the Beacon Alumni to reflect on their work; the opportunities they have created to include a rich, nuanced, decolonised curriculum; the challenges they have faced; the whole school curriculum audits that have taken place; and the impact of being involved in the TIDE Beacon Fellowship. For many years, teachers and students have campaigned for changes to be made to the teaching of history, with the Runnymede Trust calling for the teaching of migration to be mandatory in secondary schools. Here, I investigate how some have taken on the challenge and sought change in their own learning environments.

Clare Broomfield, head of history at Villiers High School, Southall, explains how she has adapted the history curriculum: Working in a school where almost the entire student body is of a BAME background, it was becoming clear to me that our current history curriculum was not doing enough to show them where they fitted into, as Michael Gove termed it, our island’s history.

The course began in a way James Baldwin advocated. We were asked to consider our own unconscious bias, to be made aware of what we were bringing to any lesson on migration, empire and race that we may be teaching. The course allowed me to develop a series of lessons, based around a key enquiry question on the migration of groups to my school’s local community. Without the course I would not have had the knowledge, and the confidence, to completely rewrite our KS3 curriculum. I am now armed with the language and tools to guide the students I teach through this complex nuanced history.

Roz Morton, an English teacher at Chesterfield High School in Liverpool, shares her experience: The absolute professional joy of being involved in the TIDE Beacon Fellowship halted my descent into cynicism and provided me with both a challenge to improve my knowledge and a structure to implement something meaningful. I set about it with enthusiasm, much supported by my fellow Beacons, as we opened lines of enquiry with one another and critiqued ideas and texts together. The end result for me was a fantastic final term with my Year 10 English class as we used the texts studied on the Fellowship, paired with contemporary non-fiction, poetry and prose extracts, to explore questions of migration, empire and identity.

The ongoing impact of the Fellowship in my own school is linked to the work I did with my Year 10 class during the TIDE programme, which has now transposed into a ‘Spine Unit’ for Year 9. This approach has engaged pupils across the ability range in a much more diverse body of literature and led them into the study of Stephen Kelman’s ‘Pigeon English’ with a more readily empathetic attitude to Hari and his tribulations. The knock-on effect of sharing this work, and the lines of enquiry behind it, has been a developing awareness that the rest of our curriculum must be challenged and examined in a similar way.