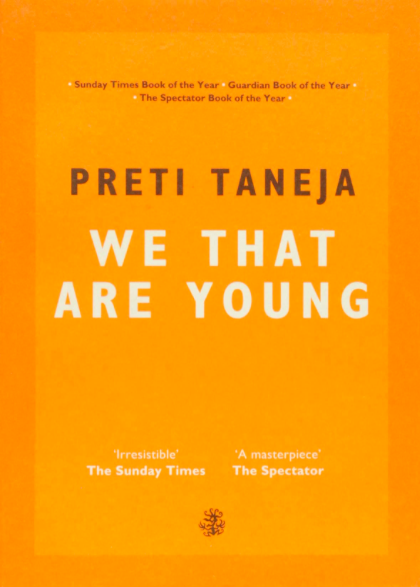

This February, TIDE welcomed Preti Taneja to Oxford as the TIDE Visiting Writer for 2019-2020. Preti teaches writing in prisons and holds an honorary fellowship at Jesus College, Cambridge. She was the 2019 UNESCO Fellow in Prose Fiction at the University of East Anglia and in April 2020, she will join the University of Newcastle as lecturer in Prose Fiction. Her novel We That Are Young (Galley Beggar Press), a translation of Shakespeare’s King Lear into a modern Indian context, won the 2018 Desmond Elliot Prize for the UK’s best debut of the year. It has been translated around the world and listed for a number of other awards, including the Republic of Consciousness Prize for Small Presses, the Folio Prize, and the Prix Jan Michalski.

Over the course of her visit, we had the opportunity to share our research with Preti, and she joined in discussions of some the TIDE ‘case studies’, a series of microhistories on transcultural figures from the period that the team are currently researching and writing. On her last day in Oxford, Preti sat down with TIDE DPhil candidate Tom Roberts to talk about her impressions and experiences of the project so far.

What was your impression of TIDE and you time in Oxford these last few days?

I have not used this week for personal research but instead used all of you as a living library. I had access to your online outputs earlier, but not you thinking or talking about your own and each other’s work. It’s unusual and a great privilege to see such interdisciplinary research as it happens; to listen to these kinds of conversations, and to see how you think and respond to your individual case studies. If I’m not physically here, I don’t get to observe these conversations between you, and I don’t get to ask you how you feel about me making artifice about your research. These are the ways fiction writers think and we don’t get to research often.

We definitely felt challenged by some of your questions! Yesterday you asked us what we thought about our individual case studies as people, and our collective reaction was to push back: ‘We have to work with what we have, and the evidence only gives us a small insight into their lives.’ ‘We’re hesitant to make comments when we are so far removed from their experience.’ I started thinking about his again, and – speaking for myself – I’m not entirely convinced by these answers. We do make these comments and we do inhabit them.

Yes, on Day One during our chat in the common room, I asked you all who you identify with the most. There was a lot of laughter, and everyone was saying ‘well, such and such is like me,’ or ‘this person got under my skin the most’. Yet by Day Two or Three, when we were having more academic and more formal discussions in college spaces, your responses changed. ‘No, no, no we’re all historians!’ If I only record the second conversation instead of the first, then the archive will never show that actually you’re just as possessed by these people as you are possessing them.

Like you say, a lot of it comes down to the space we’re in when we talk about them, and whether we have our formal researcher hats on or not.

And part of what I do as a fiction writer is observe this transition. Those are the places where human behaviour is so interesting to me, and I start thinking about how your case studies might have performed themselves as well? When they sat down to write, what were they doing 30 seconds before? How would they talk about the work they were doing before they decided that this is the formal space in which they’re going to leave their legacy? That’s the material for me, the little interliminal spaces, those interstices of time, that’s where the imaginative work gets to be done. There are probably clues in the text, in the source material you’re working with, but they’re also in how you decide to write up the narratives of these people, because you’ve got that understanding of their characters, and you might not even realise it. That’s what I’m going to be looking for.

Of course, I’m meeting you all in Oxford, so I have no idea how the experience of doing this would have been in somewhere like Liverpool [where TIDE was based till September 2019], which is a very different space and has a different nature to the city. The period you’re studying is very alive here in Oxford – it’s in the stones, the panels, portraits, rituals – it was probably legislated here. Does it feel different now than in Liverpool?

Strangely I felt more connected to what we’re trying to do when we were in Liverpool because what immediately happened after our period is Liverpool. It was a small settlement in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but by the eighteenth century it had obviously become a massive trading centre, a cornerstone of the colonial project. And the legacy of the people we study and that expansionism felt very alive and very much embedded in Liverpool as a city and a physical space, despite the fact that I don’t think a single one of the case studies had a connection to the city. Yet it still somehow felt more real and more relevant. I don’t feel the connection so much here, if that makes sense?

It does makes sense, but it feels like a dangerous statement in a way, and because you have that feeling, I think it matters more that it’s here because the work needs to be done here. Liverpool is a very self-aware city, it understands its transatlantic slave trade and colonial history, it has a strong left wing political identity, and it is very good at organising. The quiet here has a kind of charge to it, and the voices that you are listening to, and the ways in which these ideas were beginning to be set down on paper – these ideas that were then implemented in Liverpool – that is a structure of society. You do the thinking here and the policy making here, and they have to live with the reality over there. When you enter into the heart of empire, into the heart of colonialism, it’s very quiet. It’s years and years, decades and generations of cultural silencing that pretends all we’re doing is thinking. We can cry - ‘Look at Liverpool! Look over there!’ while the actual crux of violence is here. That’s why it’s important that the project is here, to be part of that moment and deconstruct some of those things. You’re all looking at the beginnings of colonisation, and in doing so, the project seems to be all about decolonisation.

Yes, absolutely. It challenges notions about how early modern people understood the world and their place in it during the period. It’s trying to get to grips with the complexity of this understanding, and how it was embedded in the very language. I feel like this is at the heart of research like TIDE: Keywords.

What’s brilliant about Keywords is the particularity about the words you’ve all chosen – ‘foreigner’, ‘stranger’, ‘subject’, ‘citizen’, ‘denizen’. They ask all these perennial questions: what do these terms mean to us now? What negotiating do we have to do to prove we’re citizens? Who gets to decide? How are we going to use language to keep people in? Or keep people out? What I think is particularly great is that you’re not just thinking about these perennial questions but asking why they are perennial questions. It’s been four hundred years, Communities are once again suffering state sanctioned violence over these questions in India, in America and here in the UK.

On a theoretical note, it’s also important that you come to these questions from an English literature and textual point of view, because when you come to early modern texts like Shakespeare and you come to these words and you think ‘there is a connection I want to make,’ it’s vital to have those etymological traces so we know we’re not misrepresenting how someone spoke in a play. And one you know that, then you can work with the language and the possibilities.

I think about that a lot in my own work. It’s flipped my understanding of these plays and the period on its head. The use of one word like ‘stranger’ or ‘alien’ in one line completely changes how you think about that play, what’s happening, and its relation to that moment.

It’s essential to understand that, and it highlights the problems in our education system that are feeding into contemporary political debates on who belongs. I’m not sure if those failures, gaps, and elisions have evolved or were decided on or ‘just happened’, but what I do know is that this project is filling a gap which is way long overdue to be filled, because it’s only by understanding the roots of how these words inform our understandings of others and of people that we can actually start to change our lives. To try to actually model what you guys are doing here which is having a shared conversation about how to understand and how to be.

There is a lot of push back against this kind of work. That recent Telegraph article on the ‘woke’ brigade ‘cancelling’ our beloved Shakespeare is an obvious example, and the blatant racism and ableism in using an image of actor Nadia Nadarajah as Celia in As You Like It for the accompanying picture.

You know I think about this a lot in my own academic work and fiction writing. Shakespeare is the ‘national bard’, and what this actually means is there are two reasons why Shakespeare is so popular over the world. First one, the elasticity of his language, the range of emotion, the vastness of his understanding of human nature, and so on. The rest of it is colonialism. You can be a literary genius in your own languages and never get translated, disseminated worldwide.

The afterlife of Shakespeare is what made Shakespeare!

Absolutely, and this is why I work with him the way I do. There are things to be said about empire and belonging through the language of Shakespeare, and Shakespeare understood that. He can feel ‘untouchable’ at times because of who decides who gets to learn what and who decides what’s on the curriculum. And that is where the joined up thinking of what you are doing comes in. One of the main reasons for why I agreed to taking part in the TIDE project is that I grew up as part of this education system that didn’t tell me why I was born in the UK. The first time I encountered partition in school was with Lear.I’d grown up with stories of the British in India, of Partition violence, but when your mum tells you story about a man who came and drew a line without ever having been to the country, about all those millions dead, about a house locked away in a place your own grandmother could never go back to – you’re just thinking ‘alright Mum, this is fiction, or science fiction’. The British system undermines out own belief in our own mothers’ oral stories. And then you see it in school and your teacher is telling you this is the canon and you need it to pass your A-Levels, you’re suddenly thinking, wait a second this is a story I know. The happy product of this experience is We That Are Young,a book that I’m very proud to have written, but it’s not ok to have had that gap. And as I’ve worked in youth services, prisons and across the UK in disadvantaged areas with children, teaching them to do heritage projects, or think about representation in museums, this comes up again and again and again. These kids have no idea why they’re here, and this gap makes them susceptible to all kinds of vulnerabilities that mainstream culture and politicians are happy to exploit. So I love the fact that the project is thinking about and tackling that through the teaching workshops, and the policy report with the Runnymede Trust, as well as doing this core research to retrace the origins of language. But something that has come up that concerns me slightly is that if you only have the sources to go on, can you as historians ever avoid just re-inscribing the violence that has been inscribed?

We’re continually wary about this. A key source for my work is the migrant census surveys taken in London throughout the late sixteenth century. When you look at the manuscripts, you might not realise at first how these migrants who have travelled to London and set up shop all over the city have been recorded by parish and ward. So already we have this political and ecclesiastical spatialising framework imposed on these people, dictating how we think about their lives. So what we have to do here is just go in aware of the politics of the archive and the politics of the documents we are working with and keep reminding ourselves why things are being recorded in the way they are and why somethings are ignored entirely. We can then try to fill these gaps and emissions using other source materials, which I think is where the interdisciplinary nature of the project comes in.

Yes, I think this is where literature can help. I think what is particularly illuminating is ways in which playwrights, poets, and essayists of the period were discussing and interpreting statehood and law. The fact that Shakespeare had the imagination that he did – with people transmuting bodies, upturning social orders, and imagining dream spaces – tells us that there was intuitively something about questioning power that was possible, surely? Lear is set in a pre-Christian moment to bypass blasphemy and treason laws. So it is that legal system that generated the constraints that put Learin a pre-Merlin place and time and yet that’s what has given it it’s longevity. It’s set outside a Judeo-Christian understanding of time, though of course that eschatological thinking does saturate the play. That he’s doing this shows that he’s trying to get around rules and critique them at the same time.

You translated King Lear into a modern, Indian context in We That Are Young. Was there anything about this process of translation that you found difficult? Were there any ideas in Shakespeare’s Lear that resisted the story you wanted to tell?

No, not at all. The Indian context is perfect for this story. Obviously, you can take Lear and use aspects of it and make lots of different kinds of narratives. One of my favourite Lears is Edward Bond’s, which is just this completely Brechtian annihilation, and an extraordinary piece of theatre. And obviously he doesn’t stick solely to the characters and solely to the plot, he changes them in ways that are striking in themselves. But fidelity to the plot was a decision that I made. For political and aesthetic reasons, I wanted to see if I could take absolutely every aspect of this play and make it work in India, and it did. One of my favourite moments to write was this kind of weirdly boring scene of the play, when Kent is locked in the stocks. He has this line ‘Fortune, good night. Smile once more. Turn thy wheel.’, and for an Indian context you have the principles of dharma, karma, samsara: life is a circular thing, and faith, religion, spirituality turns into how we live now, and what our role is in life and our duty and so on, and it’s such a perfect chance for translation and transposition, so for some of those Shakespearean things I was able to find Indian concepts, or Hindu concepts, because most of the characters in the novel are Hindu.

The thing I did find difficult was that – because the play’s language means so much to me, and I’ve know it like a familiar song – as a writer you want to find your own voice that fits the world that you’re making. When you’re working with Shakespeare, one of the dangers is that the lines are so iconic, and so deeply in us, that we don’t realise when we’re just quoting. And if I just quoted a line it would have meant that in whatever scene I was translating, the reader would have immediately been like ‘Oh well, I’m out of the world now and into Shakespeare’s’. The bones stick through, and that’s what’s really difficult, and it took a lot of drafts. I had to find a way to get the text hidden inside the text that I was writing.

Finally, how do you think your work with TIDE will evolve?

I’m going to go away and think about what we’ve spoken about, and read your research, and I’m going to write a piece of fiction, a short story. I don’t know what about yet, but I’m going to go over my notes and something will come up, I’m pretty sure of that – it can’t not! We’re also going to run a creative writing workshop for black and ethnic minority students and staff in Oxford using your archive material, and I can’t go into the details now, but we’ve just heard that we’ve been given funding for a music event through the TORCH Humanities Cultural Programme. It's going to be a ghar-style salon, bringing British South Asian spoken word poets and music into contact with the TIDE keywords. I want to bring some joy in our fraught cultural moment by putting on an event that will transport people with sound and poetry, and make them feel good.